THIS MONTH IN KOREAN-AMERICAN HISTORY - Jan 2026

The First US Koreans :

Hardships, the Korean Resistance, Korean Pioneer Aviators and California Rice Farmers

By Sharon Stern

This month we are exploring some of the first Korean Americans and their participation as a diaspora in the fight for independence during the occupation by Japan that started in 1910 and specifically the first Korean aviators, who were trained in Northern California. This isn’t a piece of history that most Americans, Californians nor Koreans know.

I generally don’t speak in the first person in these articles, but this particular corner of history touches me personally. I grew up and live in Northern California, very close to where Korean resistance aviators trained. I grew up in a place surrounded by rice fields and went to school with rice farming families. In order to get to the highway, we had to drive through miles and miles of rice fields. We were required to study Californian history in school. And yet, some critical moments in the history of the Korean resistance, the connection of California rice farming to Koreans and of the beginnings of the Korean-American story took place right here and I never heard about any of it until a couple of years ago and then only because I was searching for the information. It is history that I feel like everyone connected to Korea and who lives in this country should know. It is still remarkably difficult to find details of this history and I hope that can change. I hope that by bringing you this history, you will become curious and want to know more.

This is the story of the Willows Aviation School and key Korean-Americans that made it possible. The Willows Aviation School was the first combat training school for Korean pilots and existed during Japanese occupation. In order to tell this story well, we need to briefly follow the path of the first Koreans leaving their homeland. It feels a little like a really long tease before we get there, but it is important to see the progression of events that made the Willows Aviation School both important and possible.

Most of the readers are living in an urban area. You probably don’t have any idea what it is like to live in a rural place. A lot of Northern California is rural. There are many miles between towns. When you go to a doctor’s office, there may be people from four or six counties in the waiting room. The main entertainment for people is high school football and bars that are out on isolated roads where if you are not local and white, you should not go in. That’s how it is today. In the 1910s and 1920s, there were no large roads connecting these places. The railroad ran north and south in California and farms were miles away from the railroad depots. Willows had less than 800 people in the surrounding area. That’s the physical context for our story.

Japanese Occupation of Korea

Feature piece of the Looking Back at the Independence Movement of Korea Exhibition. (Suh Se-ok. The March 1st Independence Movement (detail). Korea, 1986. Ink and color. 776.6 x 127.2 in)

We’ve covered the history of Korea and Koreans right before, during and after WWII in a couple of ways in the history articles over the past couple of years. For a deeper look at the history of Korea during WWII, you can read this article from our July 2025 newsletter. For a better understanding of how Koreans were dispersed into a worldwide diaspora, you can read this article from our August 2025 newsletter. For an in-depth look at the March 1 Movement of 1919, you can read this article from our March 2025 newsletter. We will review just a few important details below.

From 1910 to 1945, Korea was ruled by the Empire of Japan. As early as the late 1890s, Japan’s influence in and over Korea was already increasing. Japan worked systematically over this period to erase Korean language, culture and identity. At the same time, Koreans were dispersed forcibly by Japan throughout its Empire in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Many other Koreans left to get away from what was happening on the Korean peninsula. This was an incredibly painful and difficult period for Koreans.

It's important to pause for a moment and reflect on the fact that no one, in general, wants to leave their homeland – the place where everything is familiar. People who migrate usually do so by force or extreme need.

Korean Resistance Organizes

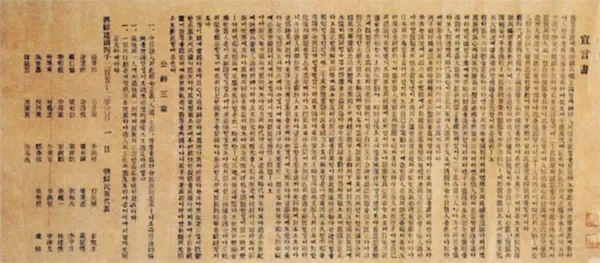

Korean Declaration of Independence (3·1독립선언서)

In 1905, Korea became a protectorate of Japan and in 1910, Japan annexed Korea. Even before the “Japanization” process of Korea progressed, Koreans who had escaped to Russia and China and those that were already living abroad began to organize.

In January of 1919, Emperor Gojong of Korea died suddenly, which started rumors circulating that he had been killed by Japan and anti-Japanese feelings began to rise. On February 8, students in Tokyo published a Declaration of Independence from Japan. On March 1, inspired by the declaration made in Tokyo, people in Seoul made their own declaration of independence. The same day, protests took place in many other cities. Protests spread across the country and took diverse forms. The brutal Japanese response led to many Koreans being persecuted, tortured and massacred. Subsequent protests occurred in diaspora communities in Manchuria, Russia and Hawai’i.

After the March 1 Movement began, many Koreans fled the peninsula. A group of leaders gathered in Shanghai and formed the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. Both the Provisional Government and resistance movements to free Korea were intimately tied to the Korean American diaspora communities, especially in Hawai’i and California.

First Korean Americans

What is Diaspora?

The definition of a diaspora comes from the original dispersion of the Israelites out of the land of Israel, as written about in the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible. The definition goes beyond just the displacement of people from their homeland. It includes an involuntary reason for moving. It also includes the desire of the displaced people to maintain their culture, their language and the heritage. It embraces the effort to not lose the connections to one’s homeland. At the same time, a diaspora usually fiercely defends the new land that they call home.

First Immigrants

Seo Jae-pil

Dr. Philip Jaisohn, 서재필. The photo was taken in the U.S. when he worked as a physician.

The very first well documented Korean to have settled in the US was Seo Jae-pil or Philip Jaisohn, as he was known here. He had been involved in the failed Kapsin Coup in 1884 and fled in exile to the US. He became a doctor here, the first Korean to do so, and wanted Korea to be able to move away from Chinese influence, without falling into the control of Russia or Japan. When the March 1 Movement started, he dedicated his time and resources to the freedom of Korea, even though he had naturalized as a US citizen – the first Korean to do so. He was offered a position in the Provisional Government of Korean, but refused and instead decided to work for Korea’s freedom and for Korean-Americans from within the US. He worked to convince the US government that they should support the independence movement in Korea. He started a newspaper published in Hangul to help educate Korean-Americans. He bankrupted himself for the cause and had to return to practicing medicine, doing important biological studies and publishing in medical journals. He was able to return to Korea after liberation at the end of WWII and before he passed away in 1951.

Seo Jae-pil’s story is amazing and inspirational – filled with rich details we can’t cover here. His work was key to connecting the Korean diaspora across America and, therefore, to making the Willows Aviation School possible. There are books written about his life, if you are interested. There are multiple memorials to him in Pennsylvania.

Dosan Ahn Chang-ho

Dosan Ahn Chang-Ho during the years he worked for Shanghai Korean provisional government.

Ahn Chang-ho, also known as Dosan, and his wife Yi Hye-ron, were the first couple (as a pair) to immigrate from Korea to the US. Yi Hye-ron was only the second Korean woman to immigrate to the US. They arrived in San Francisco in 1902. Ahn enrolled in a primary school in California to try to learn English. They had a difficult time finding work in San Francisco because of the extremely strong anti-Asian atmosphere. The moved to Riverside, near Los Angeles, in 1904, encouraged by friends working on citrus farms there. More about his work in Los Angeles and beyond are discussed below.

Dosan Ahn Chang-ho went on to be one of the most important Korean Americans and Korean Independence Activists in history. His formation of the Korean National Association (see below) as well as Gongnip Shinbo, which became Sinhan Minbo Korean-language newspaper that helped settle and educate many Korean immigrants coming to California from Hawai’i and other parts of Asia. His activities to educate Korean-Americans about the Korean Independence Movement and collect funds for their efforts cannot be understated.

In 1926, Ahn returned to China and worked with the Independence Movement. He was arrested at least five times by the Japanese and tortured. He died in 1938, after his final detention in 1937.

Dosan Ahn Chang-ho is a great Korean hero and deserves an entire article focused just on him. We will make that happen soon. For now, know that the Willows Aviation School could not have happened without his tying the Provisional Government of Korea and the KNA in Hawai’i, California and Pennsylvania to the Korean-American California rice farmer that made it happen.

Koreans Come to Hawai’i

Sugar Cane plantation workers.

It is widely believed that the first group of more than 7,400 Koreans to come to the United States came to work on the sugar plantations of Hawai’i between 1903-1905, beginning on January 13, 1903. This is the reason Korean-American Day is celebrated on January 13th. The Korean Empire had, for the first time, issued English-language passports to these immigrants so that they could go to Hawai’i. Prior to this, you had to have specific, written permission by the King or Emperor to travel outside of Korea. The concept of a passport had only just been embraced.

Japanese laborers had been working in the sugarcane fields, but they were striking and the plantation owners recruited Koreans, against the emigration laws at the time and they were only told partial-truths regarding the work they would be doing. Plantation owners wanted another race of workers to block the unionization efforts of the Japanese. Japan stopped the migration once they had signed the Japan-Korea of 1905 and Korea was a protectorate of Japan. The conditions on the sugar plantations were deplorable and Korean laborers suffered greatly. Koreans were trying to escape political turmoil and famines due to extreme weather episodes in Korea and ended up in an equally or perhaps worse situation.

The Role of Christianity in Korean Immigration

Korean Christian Church in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, founded in 1918 by Syngman Rhee, who would eventually become the first president of the Republic of Korea (South Korea). Photo by and courtesy of Ruth H. Chung.

In the very late 1800s, mostly Presbyterian and Methodist missionaries entered Korea. Catholic missionaries had been connected to Koreans and in Korea since 1603. We covered the persecution and execution of Catholics from 1791-1866 in the September 2025 newsletter.

The role of Christianity as a motivator for Koreans to immigrate to the US is significant. The Protestant missionaries brought messages to Korea of universal equality, which ran counter to the Confucian teachings that were central to the Joseon Dynasty. The core Christian concept of the Trinity – Father, Son and Holy Spirit, as well as the virgin birth, were fairly easy for Koreans to accept because Tangun, the ancient creation myth, speaks of a creator who fathers a son by breathing on a woman. The Bible’s teaching of a Father and a Son born of a virgin by the breath of the Holy Spirit seemed somewhat familiar.

Protestant missionaries translated the Bible into Hangul, instead of Chinese, making it universally accessible to Koreans. They taught girls how to read and write – a concept that was not permitted in the Neo-Confucian teachings of Joseon. Because Hangul is simple and logical to learn, girls and women quickly became literate. Koreans began to not only feel but understand the rigidity of the social structures they lived within. Life in another place without that rigidity seemed good.

During occupation and after the March 1 Movement began, Korean nationalism and the Christian messages of liberation, freedom and self-determination rang very true for oppressed Koreans. The Japanese brought Shintoism to Korea as well as wanting Koreans to bow to the Japanese Emperor, neither of which Korean Christians accepted. As occupation dragged on and the resistance movement grew, proclaiming Christian beliefs was, in itself, an act of resistance.

Korean immigrants to Hawai’i were very involved in Protestant churches. Protestant missionaries in Korea were also directly involved in encouraging Koreans to immigrate, telling them that they would be free to worship in the US. Korean churches in the Korean communities in California were also central and vital to those communities.

Racial Discrimination

Koreans who immigrated to Hawai’i faced contracts that forced them to stay for five years, low wages and debt to pay off their passage, language challenges and discrimination by plantation owners, managers and the greater Hawaiian society. As Koreans in Hawai’i faced the end of their initial five-year contracts and after experiencing the brutal conditions on the sugarcane plantations, a group of them decided to seek better conditions in California. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt issued an executive order blocking Koreans in Hawai’i from re-migrating to California. Anti-Asian discrimination was already strongly entrenched. When Japan annexed Korea in 1910, Koreans already in the US were literally without a country. They weren’t able to become citizens here. They didn’t want to return to an occupied land.

Koreans coming to California immediately encountered strong racial discrimination. The Naturalization Act of 1870 excluded any Asians from being able to become US citizens. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers and explicitly denied Chinese that were already present the right to become citizens. Chinese labor was a critical part of agricultural production in California at the time. With Hawaiian annexation in 1898, 12,000 Japanese immigrants came from Hawai’i to settle in California and they filled in the gap that the lack of new Chinese labor could not fill. White farmers in California made no effort to distinguish between Chinese, Japanese or any other Asian people. Because of the large influx of Japanese to California, the state then passed the California Alien Land Law of 1913, prohibiting aliens ineligible for citizenship (i.e. all Asians) from owning agricultural land, but permitted leases for up to three years. Tightening of the law was clarified in the California Alien Land Law of 1920.

Many of the first Koreans coming to California were seeking a better life than the one they had found on the Hawaiian sugarcane plantations, but faced the same and worse anti-Asian attitudes on the mainland. They also faced downward mobility, as they earned even less money for many jobs in California than on the plantations in Hawai’i. They couldn’t find work in the cities because of racism – not even housework – and that is why they turned to agricultural work.

Koreans in California and the Korean National Association

Korean National Association

The cover of the first issue of Sinhan Minbo (신한민보).

In 1903, Ahn Chang-ho and a small group of Korean leaders in San Francisco created a Korean American organization called the Korean Friendship Society, after Ahn saw Korean ginseng merchants fighting in the street and was upset at how that represented Koreans to the US. In 1905, the organization changed its name to the Mutual Assistance Society and the first Korean-language newspaper was established, eventually becoming the publication Sinhan Minbo (신한민보), which continued to be published through the 1980s.

In 1905, Ahn Chang-ho and his wife moved to Riverside, California, where Ahn worked on a citrus farm on Pachappa Avenue. He saw that there was a need for a Korean American employment agency to help Koreans find work (they often had language challenges) and established the Korean Labor Bureau.

Because of Ahn’s presence, the KNA was also present and very active with the citrus workers. After Japan’s Prince Ito was assassinated by a Korean independence activist, An Jung-geun, the KNA at Pachappa collected funds for his defense.

In 1908, Durham Stevens, a US diplomat to Japan, serving in occupied Korea, was assassinated because he publicly stated that Korea was better off under Japanese occupation. Remember that this is two years prior to full occupation by Japan. Anti-Korean sentiment in the US surged. As a result, in 1909 United Korean Society in Hawai’i and the Mutual Assistance Society and many other, smaller Korean-American organizations merged to become the Korean National Association.

By 1911, the KNA had expanded and was representing the interests of Koreans in the US, Russia and Manchuria. When the March 1 Movement began in 1919, the spirit of nationalism was renewed in Korean-Americans. Korean-Americans in California, led by Ahn Chang-do, were instrumental in gathering funds for the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai, as well as resistance operations. This deep connection of support for Korean independence in California was the motivation and foundation the led to the creation of the Willows Aviation School.

In 1913, there was a great freeze that killed a lot of the citrus trees and the industry collapsed and many of the Koreans moved north into other agricultural industries, including rice, which brought them to towns like Willows.

The Hemet Valley Incident

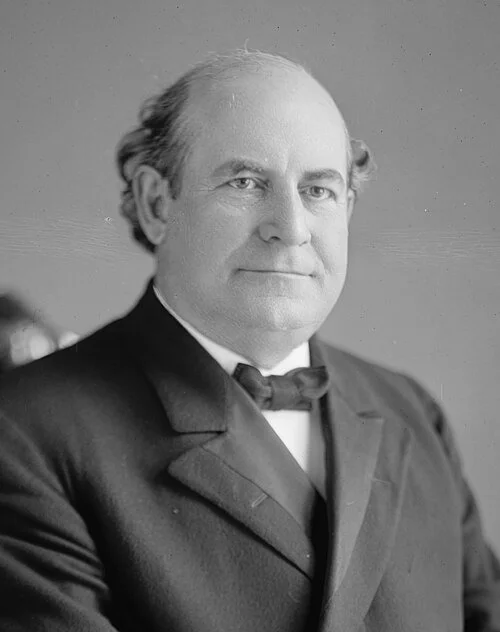

William Jennings Byran, 1910s

In 1913, 11 Korean immigrants were traveling to the town of Hemet, California, to pick apricots. White farmers threatened to kill the Koreans at the train station and they fled. The Japanese Association of Southern California asked the Japanese consul in San Francisco to intervene. Koreans who had lived in the US before the Japanese occupation of Korea argued that they were not Japanese citizens and that this was a separate, Korean incident. The US Secretary of State, William Jennings Byran, ordered an investigation of the incident. He didn’t want the already tense relationship between the US and Japan to get worse. The Korean National Association wrote to Byran, asking that the US not communicate with Japan over the incident, since Koreans were not Japanese. Byran published a press release announcing that the incident had been settled, which was a de facto recognition that Koreans were, indeed, not Japanese citizens.

The action by Byran to try to bury the Hemet Valley Incident, but which led to a separation of the identity of Koreans from the Japanese helped the Korean community tremendously through WWII. This recognition of Koreans as distinct from Japanese was tested almost immediately when six Koreans came through San Francisco, claiming to be students without documentation that they were students. To overcome immigration questioning and issues, Korean men would come in as students, even if not to traditional universities. Because Koreans now held a unique status for consideration of immigration, the six men were allowed into the US to train as pilots without all of the proper documentation.

If the Byran press release had not been published, it is very likely the Willows Aviation School could have never existed.

Korean-American Rice Farmers in Northern California

The Mediterranean-like climate of Central and Northern California allowed for the cultivation of many typically Asian fruits and vegetables, including persimmons. Rice growing in California started with Chinese laborers during the Gold Rush in 1848. In 1909, a Japanese immigrant successfully grew short-grain Japonica rice in Butte County (that’s where I live!) Rice began being produced commercially in Northern California in 1912. California rice is grown differently than in other parts of the world. Fields are trenched in long, but earthen-enclosed lines and when they are flooded, they water is shallow, compared to Asian rice fields. This is done to use as little water as possible. Asian rice farmers all had to learn new techniques in order to be successful, but let us clearly state that Asian-Americans were the beginning and development of rice in California. California rice is now a $5 billion business.

Rice had become an important source of cheap, stable food for laborers as well as for U.S. soldiers fighting in World War I. When the great freeze happened in Southern California, a number of Korean immigrants headed north to work in the rice fields. Koreans couldn’t own the land to produce rice. However, they could share in the profits of working the land. As tenant farmers, they could earn 10% of the profits from the sale of the harvest. From 1910-1920, at least 30 Korean tenant farmers produced rice, planting and growing varietals that had not been produced in the US previously.

Because Koreans were working in agriculture, they were not clustered in large cities or towns – most of them lived in very small towns in rural areas. The Koreans worked hard to save what little income they made, which was easier in rural areas where the cost of living was lower. Koreans pooled their money together in a kind of cooperative credit system to lease land. They would rotate the recipient of the credit, so that each person got a turn at having capital to invest in a lease. Koreans became known as talented rice farmers and landowners were happy to lease to them because their 90% profit was a good deal for providing the land and water.

In 1918, Korean tenant farmers harvested 210,000 bushels of rice in Northern California. Koreans also sub-leased some of their land to Sikh farmers and earned even greater profits. The intersection of Sikh, Mexican and Asian farmers in Northern California is a separate and fascinating story. It is interesting and important to note that in documentation from landowners, sub-leasers, banks, etc., Koreans always identified themselves as Korean. There were no requirements to identify race on most of these documents, but Koreans still identified themselves as Korean. When the March 1 Movement began, Korean rice farmers organized and collected funds for the KNA. In 1919, 185 Californian Korean rice farmers collected nearly half of the $88,000 in donations that went to the KNA from the US.

By 1919, airplanes, which had been tested as machines of war in WWI, were starting to be used for other purposes. Rice planting and fertilizing was much more easily accomplished from the air. This allowed for bigger crop yields and, consequently, greater profits.

There are a couple of particularly notable Korean American rice farmers in Northern California at this time.

Lee Jai-soo

Lee Jai Soo

Lee Jai Soo was a rice farmer in Maxwell, California. He had worked on the sugar plantations in Hawai’i. He worked laying the cross-country railroads of the US in Utah and Colorado, where he was recognized as a valuable leader by the white foremen. He developed water conservation techniques for rice cultivation. He was known as a leader and someone with deep responsibilities to his adopted homeland.

Behind his public immigrant, farming figure, he also fought tirelessly for Korean independence. He knew Ahn Chang-ho and worked with Korean-American organizations in San Francisco, Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. In 1907, he was one of the first members, along with Ahn Chang-ho, of the New People’s Association or Shinminhoe, formed to assure Korea’s independence.. He was later very active with the KNA.

Lee’s most significant contribution to independence was to help establish, organize and run the Willows Aviation School. He was the treasurer and helped to fun its existence. As with the next person we highlight, not even Lee’s immediate family knew of all of his activities while he was alive. In 1949, he wrote a manifesto to his children, encouraging them to embrace democracy and loyalty to America while also urging them to contribute to the rebuilding of Korea. He passed away in 1956. His and his wife’s remains were finally repatriated to Korea in 2019 and given full honors in the Daejeon National Cemetery – Korea’s national cemetery for war heroes.

We do not know enough details about this valuable Korean-American. We do know that the Willows Aviation School would absolutely not have existed without him.

You can read a little bit more about him here.

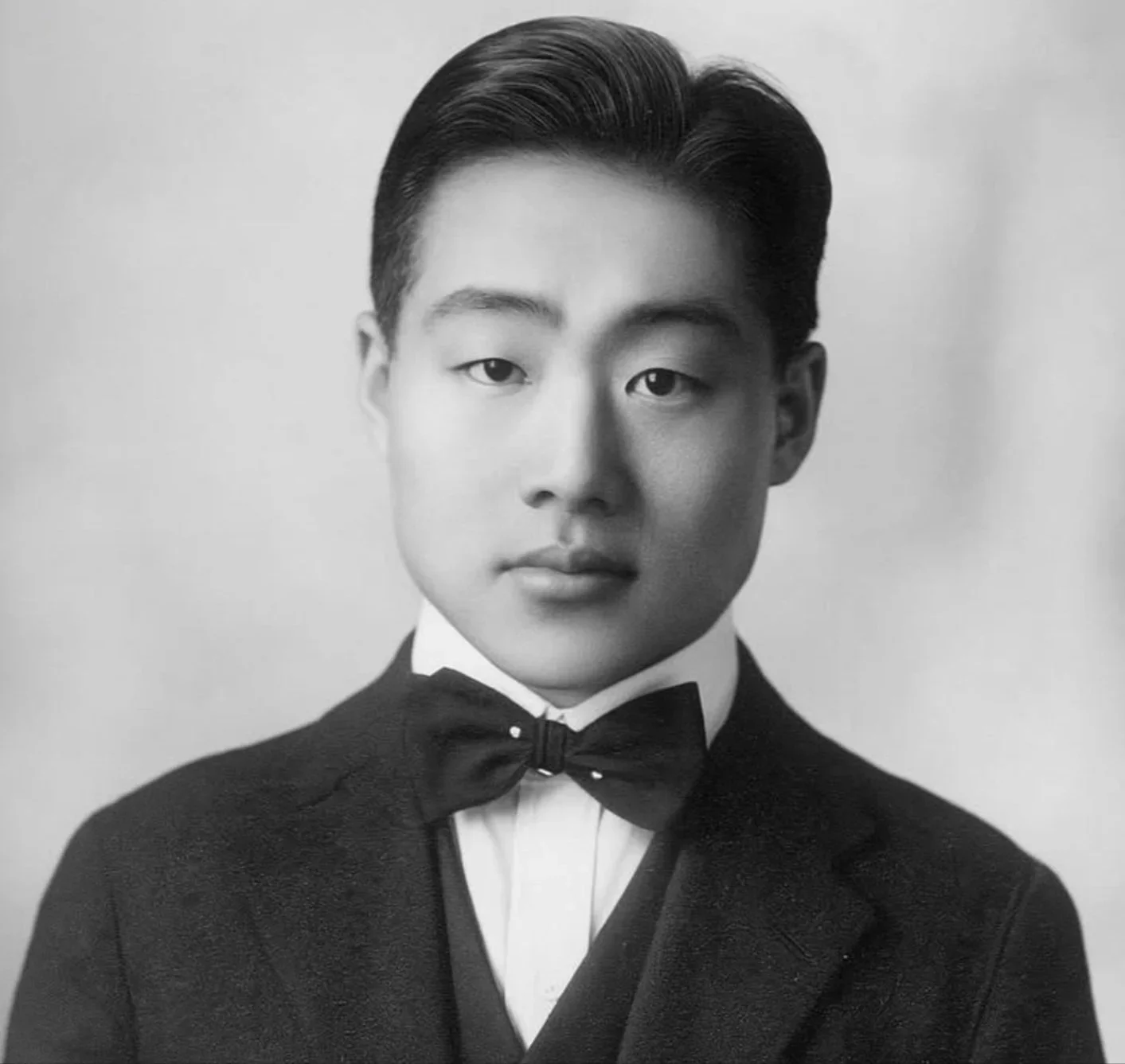

Kim Chong-lim

Kim Chong-Lim in his early years.

Kim Chong-lim came to the US in 1906 and began working on the construction of the cross-country railroads in Salt Lake City, Utah. Just a year later, he began donating what to him were very large sums of money to associations that evolved into the KNA and also to the emerging Hangul newspapers in the US. They weren’t large sums, in the general sense, but they were huge portions of his income.

In 1908, he moved to California and founded an organization to help create independence military bases in Manchuria and Russian Far East. When WWI broke out, there was a great demand for rice to be sent to US troops and he began rice farming in Willows, California. He became a millionaire and was known as the Korean Rice King.

When the March 1 Movement began, his passion for freeing Korea from occupation grew. He met Noh Baek-rin, who had been a military leader for the Korean Empire, staunchly opposed to Japan’s plans for Korea and then became the military leader of the Provisional Government of Korea. General Noh had observed the strategic use of aircraft in WWI and said to Kim, “The victor of the next war will be the one who rules the sky. For Korea to win its independence, we must have our own air force.”

Kim took this idea to heart and established the Willows Aviation School. He funded it with $50,000 of his money (close to $1 million in today’s dollars), leasing 3,300 acres in Willows, California for the school, including the abandoned Quint school, built during the gold rush. He bought three airplanes, hired instructors and mechanics and paid room and board for the students at the school.

The school opened in February of 1920 (see more below) and Kim served as the president, with General Noh as the secretary, Seo Jae-pil as treasurer and Ahn Chang-ho as a supporter and frequent visitor. Tragically, in October of 1920, the Sacramento River experienced disastrous flooding from an enormous storm right before rice harvest, causing Kim financial ruin. Despite heroic efforts, the flight school had to close. We’ll discuss this further below.

Kim continued to support independence efforts in every way that he could. When Japan struck Pearl Harbor, Kim, at 60 years old, enlisted in the California State Guard. He passed away in 1973. His remains were posthumously transferred in 2009 to the Daejon National Cemetery for military heroes in Seoul.

Korean Aviators and the Willows Aviation School

Though this photo clearly says Willows at the bottom, it is believed to be of the pilots who transferred from Redwood City to Willows Aviation School. The writing on the top indicates that the pilots were under the command of Noh Baek-Rin.

We’ve talked about early Korean immigration to the US. We’ve talked about the Korean-American leaders in the US who joined and supported the fight for Korean independence from the US. We’ve talked about heroes that were deeply loyal to both the US and the democracy and freedom it represented, but simultaneously to Korea, the place of their birth. Let’s look at this unique, though unfortunately short-lived, school for Korean pilots.

We mentioned above that General Noh of the Provisional Government of Korea had the vision and cunning to understand that if Korea could attack Japan from the air, they could win the war of independence. No country had an air force military branch yet – that didn’t happen until WWII. Airplanes had absolutely been used during WWI. At first, they were used mostly for reconnaissance and later equipped with machine guns. By the end of the war, it was obvious that they were an incredibly important tool, though flying was still incredibly dangerous.

Rice farmer Kim Chong-lim had funded several Koreans to train at the Redwood Aviation School in Redwood City, which is in the South Bay of the greater San Francisco area. This school was simply an aviation school where students could get a pilot’s license. However, Korean-Americans in Northern California had a vision to have a school specifically for combat pilots to train to attack the Japanese occupiers. The vision wasn’t just a school to train pilots but a military corps trained to fight using airplanes. The school would be a military training academy.

When General Noh stopped in San Francisco and heard of the desire to open a pilot training school, he realized this was something he needed and wanted to do. Kim was willing and able to help. Kim was not the only Korean-American rice farmer to donate to the school, but he was by far the largest and most important. The Provisional Government of Korea approved the plan for a flight school, Kim, Lee Jae-soo and others were able to put the pieces together in just two weeks, but it is assumed that Kim had already put strategic planning into place. Kim leased 3,300 acres to establish the airfield, as well as the abandoned Quint school buildings to create the school.

Cadets at Willows Aviation School.

There was opposition in both Willows and other parts of California to the school. Noh, Kim and Ahn Chang-do all fought hard to convince individuals and local government that the school was to create good American citizens – teaching them to read, write and speak English, but also training them to become strategic pilots, should America go to war again and need them. Noh stated that if the pilots later fought for Korean independence, that this fight would be an Asian one and would not come back to America, so there should be no objection to the school. The Japanese government was also closely following what was going on in Willows, California and knew details about the school.

In February, 1920 the Willows Aviation School came into being. When the school opened, six pilot trainees from Redwood City transferred to Willows and 17 others joined them. By early summer, there were several dozen students. The school was run like a military academy. Students took classes and practiced flying using a Standard J-1 airplane. When the tragic flood hit Kim Chong-lim’s rice fields in late October and he lost his fortune, funding for the school disappeared. By December, classes and flight instruction had ended. Still, 30 combat pilots were trained and graduated from the school while it was open. Most of the graduates of the school went on to enlist in the US and Chinese armies. The Provisional Government of Korea intended to open its own school in China, but never succeeded.

Two of the graduates – Park Hee-sung and Lee Yong-keun were appointed by the Provisional Government in Shanghai as Korea’s first aviation officers. Not the US nor Japan nor major powers of Europe had established separate air force branches yet at this time – Korea was the first!

Park Hee-sung

Park Hee-sung was in the first group of cadets at the Willows Aviation School. His older brother, Park Hee-do, was one of the 33 representatives who signed Korea’s Declaration of Independence on March 1, 1919. When the school closed, he transferred to a flight training school in Sacramento. He was reported to be the most skilled pilot at Willows. Despite his skills, he was almost killed in an air accident during his license exam in Sacramento, due to a mechanical issue with the plane. Luckily, he recovered quickly, but he was not able to continue with his independence activities due to complications from his injuries. He died at the young age of 41 in 1937.

Lee Yong-keun came to the US in 1916 and worked in agricultural in Northern California. Both his father and brother were arrested in Korea for independence activities. Lee had trained at Redwood City before transferring to Willows. He transferred to the Sacramento flight training school with Park, after the Willows school closed.

There were many other brave men who trained at the Willows Aviation School and, as mentioned above, went on to serve in the US military in WWII and also continued their independence activities against Japanese occupation.

The Republic of Korea Air Force recognized the Willows Aviation School as its predecessor. Willows, along with several other small, Northern California towns, later hosted one of the air fields that trained US pilots for WWII, after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Post Scripts

Willows Aviation School seems a little like a blip in both Korean and US history. There have been many what-ifs contemplated about the effects the school could have had on the outcome of Japanese expansionism and WWII itself, had it been able to stay open and successfully train large numbers of pilots that went on to fight Japanese occupation and expansion. That history, of course, will never be known. What is known is that the extremely brave men that traveled to Willows were willing to risk their lives for their independence.

The National Aviation Museum at the Gimpo Airport in Seoul has a statue of the first Korean-American pilots trained at Willows Aviation School.

There are multiple lessons in all of this. The names of Korean-Americans who gave everything for independence, such as Lee Jae-soo, Kim Chong-lim, Park Hee-sung and Lee Yong-keun should be known by all Koreans and Korean-Americans. Ahn Chang-ho and Seo Jae-pil are well known, but these other heroes need to not be forgotten. The children of these heroes served in the US military and have also fought bravely for the freedom that this country has given them.

Willows is still a small town. The remains of what was the Willows Aviation School are crumbling literally in a field of weeds. There are three buildings, one of which has been moved to a safe property, but the other two sit, falling apart next to a weedy field that was the airstrip. There is a proposed memorial to be built using one of the buildings and its contents, but an enormous amount of money needs to be raised. The Korean government has promised to pay a percentage of the cost, but the remainder needs to be raised.

There are only a handful of people who have dedicated themselves to trying to preserve what remains of this site and they are all of retirement age. It is a tragedy to think that this unique and important piece of history could disappear forever.

I think that the Willows Aviation School should be included in the school curriculums of the schools in Northern California. We learn about the great, Caucasian leaders that built buildings, profited in agriculture and made permanent marks on the land. If we understand that our past is more diverse than that, we can create a more informed and unified future.

Documentary Films

Short documentary on the Willows Aviation School with Rhew Ki-won, who is the chief fundraiser responsible for preserving its physical history

Short documentary by two UCLA professors early Korean migration and Christianity

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_4YTrWKPZY&list=PL9AcT5q3MiC2blqIGmdKdqU11g2L_3M0K&t=315s

Further Reading

Korean Aviators and Willows Aviation School

https://digitallibrary.usc.edu/asset-management/2A3BF1O0QNUL5?FR_=1&W=1280&H=667

https://www.koreanindependencelegacy.com/ancestor-stories2/project-two-llrgk-f3bhn

https://kahistorymuseum.org/kim-chong-lim/

https://apiahip.org/everyday/day-105-willows-korean-aviation-school-glenn-county-california

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willows_Korean_Aviation_School

https://www.facebook.com/people/Willows-Air-Memorial/100057788554412/

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Willows_Korean_Aviation_School

https://krcrtv.com/news/local/new-museum-to-memorialize-start-of-korean-air-force-in-willows

https://www.chicoer.com/2023/12/01/korean-performers-will-hold-concert-at-chico-state-next-week/

Korean Christians

https://hiddendrives.wordpress.amherst.edu/2021/01/14/lili-kim/