THIS MONTH IN KOREAN HISTORY - Sept 2025

persecution of christians during joseon

By Sharon Stern and Eun Byoul Oh

On September 20, the Catholic Church celebrates the Feast of the Korean Martyrs. This month we take a look at the sad series of events that shaped this history and its position in Korean history.

We live in a very divided world right now. “I’m right and you’re wrong,” dominates the way people and governments approach issues. No one should be tortured or die because of who they are or what they believe. And yet it happens every day, all over the world. Late in the Joseon Dynasty, thousands of Korean Catholics were tortured and killed because of their beliefs. As we examine how this happened, we should stop and think about how countries and individuals judge and condemn people out of fear and hatred because they are different.

Political Organization of the Joseon Dynasty

The Joseon Dynasty was not the longest dynastic kingdom, not even in Korea (that honor goes to Silla), but it did stretch for 505 years, from 1392-1910. For much of that time, the kingdom was relatively isolated and, toward the end of the 19th century, was referred to as a “hermit kingdom” – a term reserved for countries that live in almost complete isolation from the outside world.

Several central concepts that dictated the organization of Korean society during the Joseon Dynasty are critical to understanding why the persecution of Catholics occurred.

Confucianism in Korea

Dosan Seowon, Andong, Korea. Seowon played a key role in incubation of Confucian scholars.

Korea has absorbed the influences of Confucianism from the time of Confucius, around 500 B.C.E. timeframe. The ancient history of Korea is complicated and parts of it are debated, but there is no question that Confucian thought and practice have been around for a very, very long time.

Confucianism dictated how people behaved in society, both inside and outside the palace, and how every small detail of life at every level was expected to be. By the time of the Joseon Dynasty, Classical Confucianism had evolved into Neo-Confucianism, which blended some Buddhist philosophy with Confucianism, and throughout the Joseon Dynasty, scholars debated different aspects of Confucianism. Korean Neo-Confucianism schools were called seowon and the Seowon Academy buildings are classified as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Neo-Confucianism in Korea was built on three fundamental principles and five moral disciplines called Samgang Oryun 삼강오륜:

samgang:

父爲子綱 (부위자강): Children must be filial to their parents

君爲臣綱 (군위신강): Subjects must be loyal to their king

夫爲婦綱(부위부강): Wives must be filial to their husbands

oryun:

君臣有義(군신유의): Kings and subject has to be loyal to each other.

父子有親(부자유친): Sons and father have to be close to each other

夫婦有別(부부유별): The behaviors of husbands and wives have to be different from one and other.

長幼有序(장유유서): Elders and youngster has to respect each other.

朋友有信(붕우유신): Friends should trust each other.

We don’t have the time nor space to summarize all of Confucian thought (!), but we will look briefly at a couple of details.

Social Class Structure of the Joseon Dynasty

The most important fundamental principle of Joseon society was the stratification of social classes. The social class structure of Joseon dictated how an individual behaves and gets treated. During the Three Kingdoms period, prior to Joseon, Silla adopted the bone rank system (골품) from China. This was a caste system based on family lineage. Sung-gol, the highest caste, had to have both parents from Sung-gol caste. This allowed Silla to have two Queens (Queen Seondeok and Queen Jindeok) after running out of a male Sung-gol.

The social strata of Joseon. There were detailed laws that discriminated people within the Yangban class according to the class of birth mother.

After the fall of Silla, there were different stratifications of social classes. In Koryo, the nobility and aristocrat class called 귀족, Gwijok were the highest of the class system. Later, Joseon also established its own caste system called Yang Cheon system. The fundamental principle of loyalty to the king was defended in the caste system that had four castes below the king: yangban (scholars or the gentry); joong-in (middle people or middle class); sangmin (commoners – 80% of the population) and cheonmin (untouchables or outcasts). Yangban, joong-in, and sangmin class were considered Yang-in, though those who belonged to the sangmin class were discriminated against as well. The yangban, who represented 10% of the population, were those who could pass the civil service exams (that still exist in Korea) to serve in the government. The social structure of Joseon limited and discriminated against those who had a yangban father and a concubine mother from a lower yang-in class. The sons of concubines had very limited access to inheritance and government civil exams. The impossibly difficult civil service exams focused on core Confucian writings and their interpretations. Even though technically any man could take these exams, it was almost exclusively the rich that had the time and money to study and prepare for them. Those that passed were the most educated and knowledgeable individuals.

Jesa: ancestral ritual of filial piety

Jesa is observed in many households today. The ritual prepares food and drink for ancestors. The ritual is performed on the day that one has passed and during major holidays, such as Seollal and Chuseok.

Another of the three fundamental principles of Neo-Confucianism is that of filial piety. Filial piety itself is a multi-layered and complex set of ideas but is grounded in the idea that children should respect and honor their parents and ancestors. This creates peace and a literal, physical harmony in the family, which then creates harmony in the country. One part of demonstrating respect comes from the act of performing ancestral rites. There are a number of different kinds of ancestral rites, collectively referred to as jesa (제사), but the different ceremonies connect families across generations and are a tangible way to show appreciation for one’s ancestors who came before. They preserve memories, legacies and a spiritual connection with one’s ancestors, who in turn provide guidance and blessings to the living. Performing ancestral rites brings blessings from God and from the ancestors. Ancestral rites are, essentially, a form of worship of ancestral spirits. Given that one of the fundamental ideas of Confucianism denied the existence of spirits or ghosts, the ancestral ritual jesa was one of the only spiritual rituals performed officially in Joseon. Other forms of spiritual rituals, including shamanistic rituals, were technically forbidden by the laws of Joseon.

남녀유별: The differentiation of man and woman

Women covering their faces while in public using (장옷) Jang-ot. Joseon emphasized how women and men had to be different. 남녀칠세부동석 (namnyeochilsebudongseok) was the rule that when a girl and a boy becomes seven years old, they should not be seated in the same room.

The third fundamental principle of Neo-Confucianism was differentiation between men and women. During the Joseon Dynasty, women lost many of their previous freedoms and the interpretation of this Confucian principle was much stricter in Korea. Women, especially yangban women, were not to be seen in public, which is why they rode in palanquins (가마). Women of other classes were supposed to cover their faces in public. Sleeping quarters for men and women were separate. Women were not taught to read or write and even those that did learn were not allowed to learn hanja – the Chinese characters. Women did not participate in the jesa ceremonies.

The yangban were divided into family clans. The king (and subsequently everyone else in society) was not allowed to marry into the same clan of his family. This created diversity from the palace all the way throughout society, but it also created competition. Clans vied for power and influence. Over the timeline of the Joseon Dynasty, clans merged and divided. The law that banned Koreans from marrying someone with the same clan name (last name) existed in South Korea until 1997, until the Constitutional Court of Korea overturned that law. We will spare you a list of all of the clans and factions over the history of the Joseon Dynasty (though you may have heard of Soron, Namin, Noron mentioned in K-dramas), but it is important to note that these clans and factions adopted differing interpretations of Neo-Confucianism and this led some to be open to Western ideas and religion and some to remain very much opposed.

Religion in Joseon dynasty

There is a debate among scholars whether Confucianism should be considered a religion, mainly due to the fact that Confucian thoughts do not discuss the issue of the afterlife. While Neo-confucianism was at the core of Joseon society, Buddhism and Shamanism still maintained a strong foothold in Korea.

Buddhism

Buddhism maintained a strong influence over Korea for milennium.

Buddhism entered Korea during the Three Kingdoms Period, coming in through China. Korean Buddhism is a unique form of Buddhism that unifies different branches and interpretations of the religion. Although Buddhist thought persisted, Buddhism was suppressed throughout the Joseon Dynasty and separated from political thought that was dominated by Confucianism. The persecution of Buddhism was particularly strong throughout Joseon partly due to the fact that Koryo, the Kingdom prior to Joseon, was a Buddhist Kingdom. Joseon was a kingdom that was founded after overthrowing the Koryo Kingdom. Different kings (and their queens and queen dowagers) held differing opinions about Buddhism, some favoring it much more than others, but after the Japanese invasions of 1592 and 1598 where Buddhist monks helped to repel the invasion by forming rebel militias, Buddhism was quietly tolerated. Because Buddhism was prevalent in Japan, Buddhism was tolerated after Japanese occupation, but its management was tightly controlled by Japanese systems.

Korean shamanism

A Joseon dynasty painting of Hyewon Shin Yun-bok (申潤福: 1758-early 19th century)’s 무녀신무 (巫女神舞) Munyeo-Shinmu The dance of Munyeo, a shaman.

Korean shamanism, known as musok (무속), and the practitioners, known as mudang (무당), pre-date Confucianism or Buddhism in Korea, traced back to at least 1000 B.C.E., and musok is considered a folk religion. It is a polytheistic religion and being a shaman was one of only four jobs that a women could hold during the Joseon Dynasty. But the Joseon Dynasty did not look favorably on the practice of musok and although they shared beliefs in spirits, they did not agree with the rituals the musok practiced and mudang were of the cheonmin caste, though the government sometimes called upon their insights in times of crisis. In reality, many people during the Joseon Dynasty combined beliefs from Confucianism, Buddhism and Shamanism.

Introduction of Christianity

Yi Sugwang’s Jibong Yuseol (지봉유설)

Although there are stories of a French priest accompanying the Japanese invaders during the Imjin War to Korea in 1598, this history is not well substantiated and is debated. Christianity is believed to have first entered Korea in 1603 via China. A Korean diplomat, scholar and military officer named Yi Sugwang was sent to the Ming Dynasty as an emissary. There he found several books on Catholicism written by an Italian priest and theologian named Matteo Ricci, who was living in China. Yi Sugwang was interested in Western literature and considered the books a representation of Western culture. When he returned to Korea, he was a high-ranking government official – Chief Council – and he emphasized adopting Western ideas to strengthen the nation, including the feeding and housing of the poor. He wrote a 20-volume encyclopedia called the Jibong Yuseol (지봉유설).

Johann Adam Schall von Bell

Yi Sugwang’s was one of the primary scholars to advocate for silhak (실학) social reforms to the rigid structure of Neo-Confucianism that dominated the Joseon Dynasty. Silhak scholars advocated for land reform, tax reform, greater equality of peoples and relief of the suffering of peasant farmers. Yi Sugwang advocated for acceptance of Western medicine, science and social structure, in addition to Christianity. Yi Sugwang’s acceptance of Christian beliefs lay the groundwork for the spread of Catholicism in Korea. Before any missionary priests arrived in the country, the writings of Matteo Ricci were guiding early Catholics in their belief and silhak scholars were converting to Catholicism, seeing Christian theology as aligning with their ideologies of egalitarianism.

It is important to mention Crown Prince Sohyeon, who was held hostage in China around 1637, after the Qing invasion of Joseon, had interacted with Johann Adam Schall von Bell, a Jesuit Priest. Although it is unclear if Crown Prince Sohyeon was influenced by Catholic beliefs, or to what extent he was willing to accept the new ideology, the Crown Prince had written letters to Adam Schall, and tried to advance Joseon’s science and technology by learning advances from the West. The Crown Prince returned to Joseon and died soon after. He was found mysteriously bleeding from the head. His death has been a debated topic for Korean historians, as also noted in many historical dramas such as My Dearest, but one thing has been recorded in the records of Joseon is that King Injo, the Crown Prince’s father, was paranoid about the interaction between the Crown Prince and Johann Adam Schall Von Bell and did not want to see Catholicism enter Joseon.

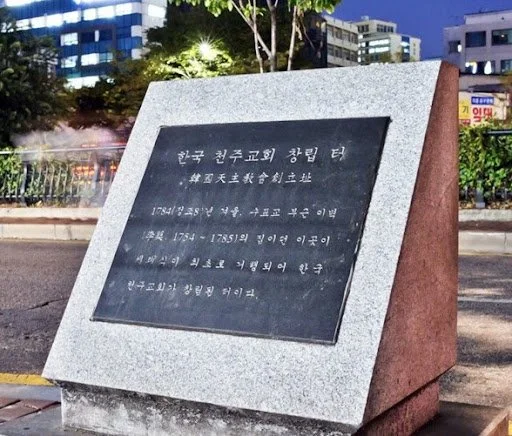

Yi Byeok was another silhak scholar who read books on Catholicism brought in from China by Yi Seunghun in 1783 and after studying them carefully, converted and began converting others. He was imprisoned in his house and he and his family were tortured and killed.

A monument stands where Yi Byeok’s house once stood. The monument states that this was the first place where Korean Catholics first met.

In 1783, Yi Seunghun and his father went to Beijing and on the urging of Yi Byeok, met with a Catholic priest there. Jeong Yak Yong, who you will get to read about briefly later, was the brother-in-law of Yi Seung Hun. He was baptized there in 1784. This was the first Korean of the yangban class to be baptized as a Christian and he returned to Korea with more books, rosaries and crucifixes. Yi Byeok convinced Yi Seunghun to baptize him (even though he wasn’t an ordained priest) and other silhak scholars, including Kim Beom-u. Kim Beom-u was a translator by profession. They began to meet at Kim Beom-u’s house on the hill where Myeongdong Cathedral sits today. The authorities raided the house, thinking it was a gambling den, but were embarrassed to find a room full of nobles. But they were still ordered to be dispersed for propagating a new religion. Kim Beom-u was arrested and tortured and killed.

In 1784, despite persecution by the state, silhak scholars began translating portions of the Chinese Bible into hangul.

These men continued to act as spiritual leaders, until in 1789, the Vatican told them to stop, as none of them were ordained and this was contrary to church teaching. They were encouraged to somehow get a priest into Korea. It was another six years, in 1795, until the first priest came to Korea from China. The Christian community already had 4,000 believers. Korea is the only country where Catholicism was established through lay leaders alone and necessarily through the elite, since they were the only ones that could read hanja.

In 1831, Pope Gregory XVI set up an Apostolic Vicariate for Korea, separating it from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Beijing. An Apostolic Vicariate is an area under a bishop’s control where no bishop is physically present. This was official recognition by the Catholic Church of Catholicism’s strong presence in Korea and its need for support.

Confucianism and Christianity: when the two worlds clash

What were the conflicts between the predominant Neo-Confucianism of the Joseon Dynasty and the teachings of Christianity? There were several main ones.

The concept of an all-knowing, all-powerful God came into conflict with the king is the most powerful and wise person in Joseon. That God created order in the world and not the structures imposed by Confucian thought was also in conflict with traditional thought.

The idea that each person is truly equal before God challenged the idea that the yangban had earned their special places through their knowledge and that this justified the separation of the classes. It also put the subjugation of women into question.

The concept that the only one that should be worshipped is the one, true God pulled the rug out from underneath the second fundamental principle of Neo-Confucian principle regarding filial piety and the performing of ancestral rites, although still embracing respect and obedience to one’s parents.

The foundation of Christian theology was in contrast and conflict to the principal tenants of Neo-Confucianism. In order for the palace and the elites to maintain their structure and power, these ideas needed to be fought against. Although the silhak scholars found ways to combine Confucian and Christian beliefs, the other factions did not and could not do this. The sangmin were very drawn to the ideas of equality that Christianity offered, which was even more of a threat to the yangban and the palace.

There was also a general fear of the introduction of ideas from outside of Asia, which brought condemnation of a couple of other reform movements that had nothing to do with Christianity.

Persecution of Catholics

Because of the conflicts many of the yangban and several kings saw between Neo-Confucianism and Christianity, persecution of Christians began shortly after the Christian community was larger than simply a couple of scholars. Silhak views of the values of Christianity, which aligned with reforms they wanted to see happen, meant that Christianity spread fairly quickly after it was communicated within silhak circles in the 1780s.

Over the period of 1791- 1866 between 8,000-10,000 Catholics were killed in Korea.

Martyrdom of Paul Yun Ji-chung and James Kwon Sang Yeon 1791

Statue of Yun Ji Chung, located near Jeondong Cathedral in Jeonju, Korea.

Paul Yun Chi-chung, a man of the nobility, was baptized as a Catholic in 1787. He converted his family and in 1790 burned their ancestral tablets, as ordered by the Bishop in Beijing. When his mother passed away, he refused to offer a sacrifice or perform a jesa ritual which was the longest and the most important ritual in neo-Confucianism, and had a Catholic-styled funeral. His actions angered the king. He was put in a cangue and told to denounce Christianity. He was interrogated and tortured multiple times. The king ordered him sentenced to death on December 7, 1791 and he was beheaded.

The king made a proclamation against Christianity called Instruction Against Bad Religion and also sent a letter to the Chinese Emperor denouncing the Western religious influence in China.

Later in 1794, a Chinese priest, Father Ju Mun Mo, was assigned to Korea. He entered Korea on December 23, 1794 clandestinely. However, he himself became the reason for another persecution, because the government tortured many Catholics in order to find him. He was found and arrested, tortured and then beaten to death. 123 other Catholics were tortured and killed during this time. Among the beheaded included James Kwon Sang-yeon, Yun’s maternal cousin, Yun is remembered as the first Catholic martyr of Korea, and he was beatificated in 2014 by Pope Francisco. His remains were excavated in Chonam Yi Sung Ji (초남이성지) in Jeonju in 2021 along with that of others.

Martyrdom of Paul Yi Do-gi in 1798

Paul Yi Do-gi and other Catholics were arrested in 1797 and taken in shackles and a cangue to prison. All but Paul Yi Do-gi confessed, after torture, who they adopted Christianity from and agreed to adhere to Confucian doctrines. Paul Yi Do-gi would not recite Confucian doctrines, but only the Bible and then began to preach to the magistrate. Yi Do-gi was dragged around the public square by horses for 12 hours. However, Yi did not die. He was taken back to prison. He was tortured many times. Right before his death, he was tortured until his body was crushed, and his body was no longer in the shape of a person. Yi still did not die. The record states that he died in 1798, and when he was told that he would be executed, Yi praised Mother Mary, saying “성모 마리아님, 하례하나이다”, which translates to Ave Maria in Korean. Yi died in June of 1798.

Catholic Persecution of 1801

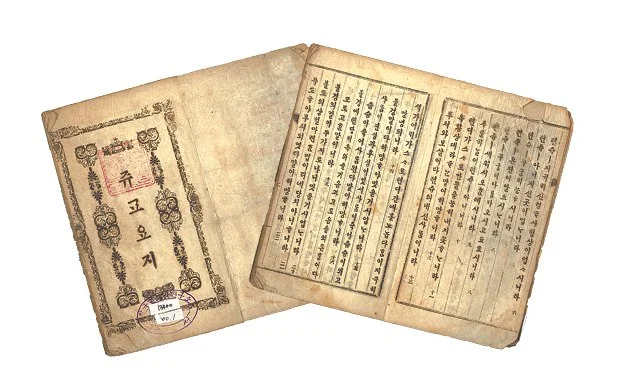

Jeong Yak Jong’s Jugyo Yoji was the first book written in Hangeul about Catholic doctorine.

In the 1790s, the Jugyo Yoji (주교요지), which was a hangul translation of the Gospels, other selected Bible passages and the catechism, was created by Jeong Yak-jong. It has been said that the Jugyo Yoji was a blend of Catholic doctrine with deeply Eastern influences. Jugyo Yoji was the first book to be written in Hangul about the catechism of Catholicism as well as translations of Biblical passages. The book aimed to preach the basic Gospels to commoners, who did not have access to education of Hanja, Chinese script. An English translation as well as the testimony of several martyred Catholics as scribed by French priests is available here. Jeong Yak-jong was arrested in 1801 and refused to denounce Christianity. He said that the ban of Christianity was wrong and he was not afraid to die for the sake of the truth. He was put to death.

He was the brother of Jeong Yak-yong (known as Dasan), who was a famous silhak scholar and is still remembered as one of the most prominent scholars of the late Joseon. It has been recorded that Jeong Yak-yong denounced Christianity after the Pope officially banned jesa practices in 1791. However, Jeong Yak-yong was still put under house arrest for his association with Christianity, even after he publicly denounced his faith.

King Soonjo was on the throne, but had succeeded his father when his father died and he was only 10 years old. His father had been semi-tolerant of the Catholics because he needed their faction for political backing. The Grand Queen Dowager, Queen Jeongsun, served as regent. She was from the Noron faction, who saw Christianity as a direct threat. The queen [dowager] began to oppress Catholicism aggressively. She also used Christianity as an instrument to weaken the political opposition and her political enemies. She successfully ousted the prominent Jeong family. Three more Catholic scholars were murdered and dismembered in 1801 for destroying ancestral tablets and holding Catholic services instead of funeral rites for deceased family members. It is important to note that the Jeong family were in-laws with Yi Seung-hun and Yi Byeok. Yun Ji-chung was Jeong Yak-jong and Jeong Yak-yong’s cousin as well. Jung Yak-jong is the father of Saint Paul Chong Hasang.

Another Catholic scholar attempted to contact members of the Catholic church in Beijing the same year, but his letter was intercepted and he was executed.

During this purge, several hundred Catholics were put to death. This is referred to as the Shinyu Persecution of 1801.

Catholic Persecution of 1839

St. Paul Chong Hasang.

In 1836, Fr. Pierre Maubant of the Paris Foreign Mission Society snuck into Korea from China as a missionary. The same year, Fr. Jaques Honoré Chastan entered Korea via Macau as a missionary. In 1839, Fr. Laurent Joseph Marius Imbert snuck into Korea, but was caught and, under torture, gave up the names of other Catholics and the other two priests. They were all tortured for three days and then beheaded.

Augustine Yu Chin-gil, was a government official who converted to Catholicism and led a Catholic community. He wrote to Pope Gregory XIV to send missionaries and priests to Korea. This effort got him arrested. His refusal to apostatize under torture demonstrated the resolve of yangban converts. He was beheaded. His son, Peter Yu Dae-cheol, was the youngest saint to die in 1839. Yu Dae-cheol was only 14 years old at the time of his death.

Paul Chong Hasang, Jeong Yak-jong’s son, who petitioned for establishment of Joseon’s Diocese and deployment of priests, was also beheaded in 1839. Paul Chong Hasang’s leadership made it possible for Andrew Kim Taegon (see below) to become ordained as the first Korean Catholic Priest. Saint Paul Chong Hasang was canonized in 1984.

Catholic Persecution of 1846

St. Andrew Kim Taegon, the first Korean Catholic priest and is the patron saint of Korean clergy. His statue is in Vatican City.

Andrew Kim Taegon was born into a Catholic family where family members had already been martyred. He went to Macau at the age of 15 to go to seminary. He also spent time in the Philippines. He was ordained as a priest in Shanghai in 1844. He returned to Korea in 1846. He was the first native Korean to become a priest. He was arrested in 1846, tortured and killed by sword. He was only 25 years old. Nine other Christians were beheaded at the same time.

Catholic Persecution of 1866-1871

This wave of persecution was the largest. It was called the Byeong-in, which refers to the name of the year that the persecutions began. This persecution is sometimes referred to as the Great Persecution. In total, nine foreign missionaries and 8,000 Koreans were killed. This happened during Daewongun’s regency and Gojong’s reign. Daewongun was a brutal politician and wanted to return the country to the old, old days of King Sejong’s rule (1418-1450). He was anti-foreigner, isolationist and a Confucian traditionalist.

The campaign of persecution began in 1866. Daewongun had asked for help from French missionaries to push back the encroachment of the Russians. Because they were not politically involved, they didn’t respond. Nine of the twelve missionaries were killed. Simultaneously, Queen Dowager Jo, who was a regent, was pushing for anti-Catholic actions. Mass executions of Catholics began. The French government responded by sending troops and war ships in an incursion that lasted six weeks after which they had to retreat. There were a number of incidents with foreign governments that made the Koreans want to shutdown outside influence even more. Mass executions of Christians continued and when there were too many people to execute, they were buried alive.

After 1871

Protestants began arriving in Korea in the late 1800s, after the Catholic persecutions, mainly from American Presbyterians and Methodists. Around 1887, Scottish Presbyterian John Ross completed a hangul translation of the New Testament. This was mass produced and distributed and the protestants began establishing schools throughout Korea, including for girls.

In 1899, a Confucian rebellion caused another 600 Christians to be martyred.

After Japanese occupation, the Japanese attempted to suppress Western influences and Christian activities were suppressed until the 1920s. The Japanese, telling Koreans they were the same people, forced Shintoism onto Korean society. The concepts of self-determination in Christianity meant that Koreans’ nationalistic ideals aligned with Christianity because of their desire to return to autonomy. During the March 1 Movement in 1919, many religious leaders joined and supported the movement. Being a Christian during the occupation was, in a way, a form of protest against the occupation.

At the end of the Japanese occupation, there were more Protestant Christians in the North than in the South. When the control of the peninsula was split and Russia had control of the North, many of these Christians fled to the South. The Korean War made most of them stay in the South. Military dictatorships that followed the Korean War had people looking for safe communities and churches helped serve that role.

Today, a sizable number of Koreans identify as Christian.

Beatification and Canonization of the Martyrs

The beatification and canonization of the Korean martyrs by the Catholic church took place in two steps. In May, 1984, Pope John Paul II canonized en masse 103 of the Koreans that had been martyred, including Fr. Andrew Kim Taegon. In 2014, Pope Francis venerated (a process of special naming of holiness) another 123 Korean martyrs and later that year he beatified (first step to becoming a saint – canonization is the final step) all of them.

In 2023, a statue of Fr. Andre Kim Taegon was dedicated in the Vatican.

FILMS

The Book of Fish – 자산어보 – 2021 - history of the 1801 martyrs

Free on Tubi and the Roku Channel, available for rent on Amazon and AppleTV, YouTube

A Birth – story of Andrew Kim Taegon – 탄생 - 2022

Available on YouTube

FURTHER READING

Politics and Culture:

https://www.coreaverse.com/2025/06/political-factions-in-joseon-more-than.html

https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/korea-from-hermit-kingdom-to-colony/

https://thetalkingcupboard.com/2016/11/15/wedding-and-marriage-in-joseon-part-1-historical-stuff/

https://gwangjunewsgic.com/arts-culture/korean-culture/harsh-punishments/

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/southkorea/society/20080820/filial-piety-greatest-heritage-of-korea

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_Buddhism

https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/15/3/280

https://artsandculture.google.com/story/iwXRbIJfYlhXIg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silhak_Museum

Catholicism:

https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/255420/who-are-the-korean-martyrs

https://uknowkorea.com/persecution-of-catholics/

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Korean_Martyrs

https://www.vaticannews.va/en/church/news/2025-07/korea-seoul-martyrs-beatification-centenary.html

https://catholicshrinebasilica.com/haemi-international-catholic-martyrs-shrine-south-korea/

https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/r-s/ross-john-1842-1915/

https://cbck.or.kr/en/CatholicChurchInKorea/History/1178?page=2

https://www.ucanews.com/news/the-catholic-church-in-korea-born-of-persecution-and-perseverence/71588

https://www.sspxasia.com/Documents/Catholic_History/For-The-Missions-Of-Asia-7.htm

https://anthony.sogang.ac.kr/Dallet/Texts/AnthologyKoreanWritingsEng.pdf

Asian practice of taking Western names:

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/opinion/20100711/asian-practice-of-adopting-western-names