THIS MONTH IN KOREAN HISTORY - Aug 2025

THE KOREAN DIASPORA BEFORE, DURING AND AFTER WWII

By Sharon Stern and Eun Byoul Oh

August always causes us to reflect on Korean independence at the end of WWII and this year we are focusing on the history of the Korean diaspora, particularly as a result of the Japanese occupation from 1910-1945. Koreans and people of Korean descent live all over the world. How many got where they are is the focus of this article, though there is no way that we can cover more than the largest groups that migrated.

The Korean diaspora is estimated to be around seven million people, with 70% living in only three countries: China, the US and Japan. The largest part of the diaspora began during occupation, but migration certainly began before that. We will take a look at how and why Koreans migrated before, during and after occupation.

Early Migration

From the Three Kingdoms period, before they were united as Koryo, Koreans were living in and trading with parts of what are now China. Various conflicts during this period saw prisoners of war brought into Northern China and what is now Mongolia.

남만병풍(南蠻屛風),Nanban byobu showing Portugese merchants interacting with missionaries and Japanese at Nagasaki port.

Japan invaded Korea twice between 1592-1598, with hopes of taking over the Manchurian region, which was weakly controlled by the Ming Dynasty, and Korea in the process. This period is referred to as the Imjin War. There is documentation of the enslavement of tens of thousands (some estimate up to 100,000) of Koreans. Many Koreans were taken to Japan, particularly to Nagasaki, where some were then sold on to other countries.. The Joseon government worked until the middle of the 1600s to retrieve its enslaved people, but only managed to return around 7,500 according to Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty.

The Manchus formed the Qing Dynasty in 1636 and the Great Qing took control of the area north of Korea from the Ming. Qing’s Invasion of Joseon in 1636 took many Korean POWs, as portrayed in the drama My Dearest, causing a diaspora of Koreans through the conflict.

Conflicts between the Qing Dynasty and Russia in the 1800s caused the movement of Koreans outside of their territory. 1,000-2,000 enslaved Koreans were also sold to the Portuguese slave trade by the Japanese. The Portuguese also took slaves directly from Korea. Most of these were sent to Macau (controlled by Portugal) and to the Philippines (controlled by Spain). Portuguese slaves were also sent to Cuba, Peru, Guiana, Suriname and Costa Rica. Individuals ended up in other European countries and trading ports. Pressure from both the Catholic church and the King of Spain and Portugal stopped most of the slave trade of Koreans shortly after the Imjin War, although slave labor of the slaves already present was still used.

Emigration started from 1860-1870 to the Russian Far East (the area furthest east in Russia, bordering China, Korea and Mongolia) and Northern China. Drought, famine and flooding forced people to move and there were peasant revolts in the south of the Korean peninsula that moved their way north and displaced Koreans as well. The Qing government facilitated the movement of Koreans into China to help cultivate land for farming, although the border was closed for casual migration. The border being closed led people toward Russia. This wave of emigration established a Korean diaspora in both Russia and China of thousands of people.

Japanese Occupation and WWII

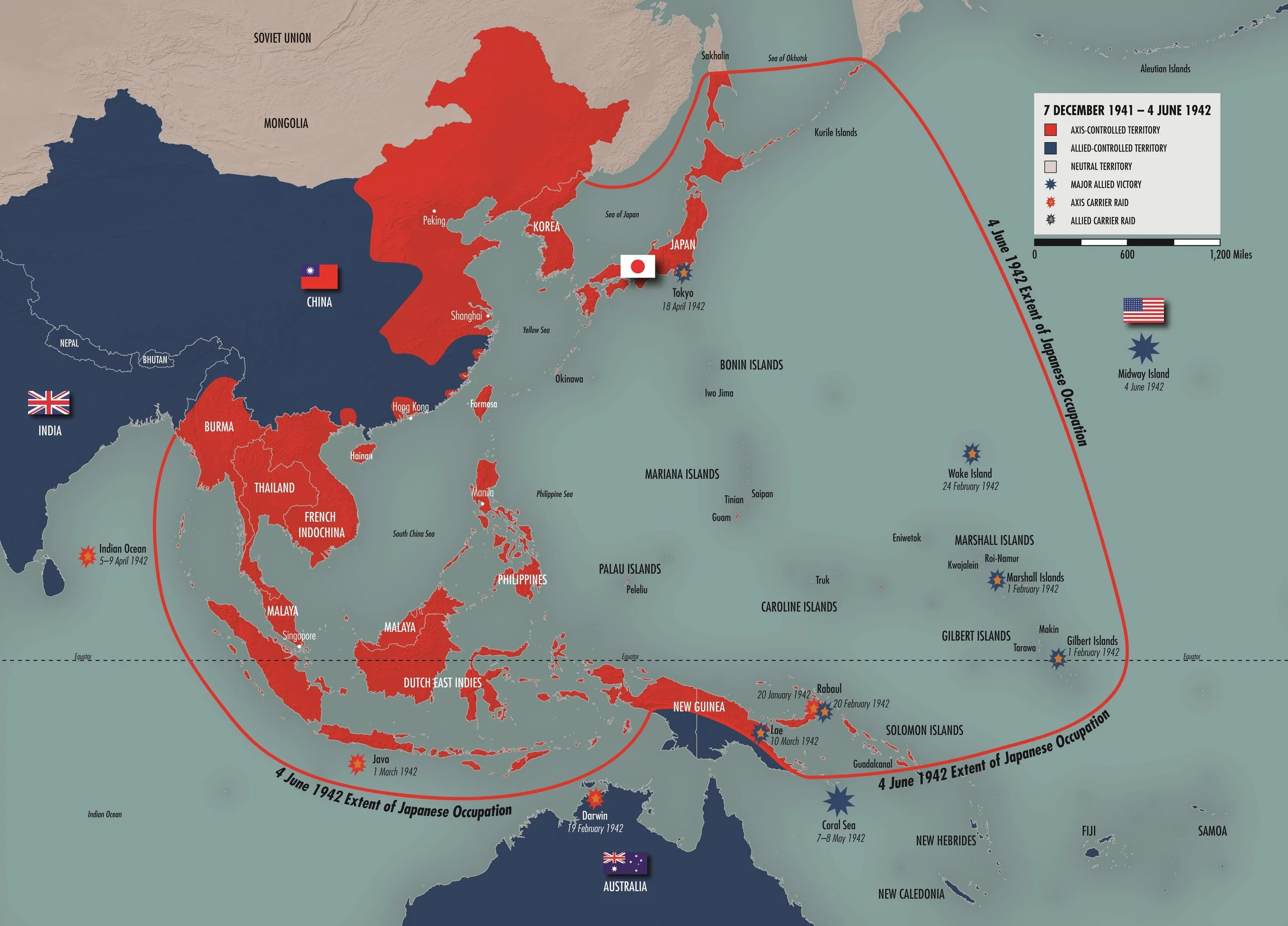

Map of the Japanese colonial empire

In last month’s newsletter, we talked about the battles between Japan and Russia for control over the Korean peninsula. These conflicts really began the large-scale forced movement of Koreans out of the peninsula.

At the conclusion of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Taiwan was ceded to Japan. One of the outcomes at the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, was that the Karafuto Prefecture was established in 1907. This took up the southern half of Sakhalin Island off the coast of Russia. Japanese had been present on Sakhalin Island since at least 1679. When Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910 and over the next decade, all three of these regions were seen as part of Japan, not just under Japanese rule.

The Empire of Japan or Imperial Japan was the nation that existed from 1868 until the end of WWII, beginning with Emperor Meiji. Ultranationalism grew throughout this time and expansionism was coupled with the belief that Japan had the entire responsibility for peace in Asia and that the emperor was a divine being. Japan’s control of parts of Southeast Asia and the Pacific by the end of WWII was expansive. Their area of control and occupation included:

Korea

Manchukuo (Manchuria)

Southern Sakhalin Island/Karafuto Prefecture

Taiwan

Kwantung (Liaodong Peninsula)

Much of mainland China

Kiautschou Bay (Jiaozhou Bay), leased from Germany

Menjiang (Inner Mongolia)

Vladivostok, Siberia

Chishima Islands (Kuril Islands, southeast of Sakhalin, near the Aleutians)

South Seas Mandate (which included part of New Guinea, the Marshall Islands, Marianas, Caroline Islands, other Micronesian islands)

Guadalcanal

Hong Kong

Singapore

Malay (Malaysia)

Parts of Burma (Myanmar)

East Timor

Manipur (now a remote part of India)

Palau

Thailand

French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia)

Solomon Islands

Dutch East Indies (Indonesia, Java, Sumatra, Borneo)

Spratly Islands (South China Sea)

Nauru

Kiribati

Guam

Some of the Aleutian Islands

Antarctica

Why is it important to think through such a long list of countries and regions? Because Koreans ended up in almost all of these places. 5,400,000 Koreans were conscripted by Japan to do work outside of Korea. Even though many repatriated after Korea gained independence at the end of WWII, some remained where they had been taken. Women were taken all over the Empire of Japan as “Comfort Women” (sex slaves) and their cultural shame afterwards meant that many could not or chose not to return home. Each individual has a story.

Koreans in Japan

After occupation in 1910, the demand for laborers in Japan was high and it was difficult to find work in Korea. Farmers in Korea were expropriated and had to find other work or become tenant farmers. Koreans were recruited and decided to go to Japan to work in mines and factories.

When WWII began, Koreans were forced to work in brutal, manual jobs. Many Koreans ended up working in military supply factories in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At least 10-20% (there are estimates of 50%) of the atomic bomb blast victims were Korean.

Any Korean labeled a dissident or rebel risked not just being sent to prison and tortured, but many ended up at the notorious Unit 731 where unimaginable, torturous experiments were done on live people. No one left Unit 731 alive.

Koreans in China

The story of Koreans in areas of China during occupation is complicated because China’s dynastic history is complex and China’s interactions with Korea are complex and go back a very long time in history. The area to the north of the Korean peninsula saw large percentages of Koreans migrate during both Ming and Qing control of the area in the 14th-17th centuries. Koreans helped develop rice production in Northern China in the mid-1800s.

When the Japanese occupation began, thousands of Koreans fled to Northeast China. In 1931, Japan took over the Manchuria region and established the puppet state of Manchukuo, which was named as a colony of Japan. Japan moved farmers whose land had been taken away in Korea into China to cultivate crops.

The inauguration of the Korean Liberation Army (17 September 1940)

After the March 1 Movement, large numbers of Koreans fled to Northeast China and many ended up in the Yanbian area of Jilin, China. Resistance groups of Koreans formed both in Manchukuo and Yanbian. Many of the migrants built Korean towns in their settlement. As we will discuss in our Book club meeting this month, Korea’s beloved poet Yun Dong ju’s family was also among the diaspora. The Korean Resistance fought the encroachment of Japanese soldiers into these regions and in 1920 fought the Battle of Qingshanli, also known as the Battle of Cheongsanli, where the losses to Koreans were greater than the losses to the Japanese, though the reported numbers are controversial. As a result of this confrontation, the Japanese moved into Yanbian and committed the Gando Massacre of at least 5,000 Koreans.

Also as a result of the March 1 Movement, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea or KPG was set up in Shanghai, China. The KPG fought both politically and militarily to regain independence for Korea. There were constant and on-going negotiations with the Chinese government to protect Koreans by making concessions and not giving in to Japanese demands. As China attempted to assert power, Koreans in China naturalized as Chinese citizens. Even so, life for Koreans in China was not easy as Chinese landowners exploited Koreans and increasing control by the Japanese removed the freedom they were seeking by migrating there. In 1932, the KPG relocated to Chongqing.

General Hong Beom Do, Commander of guerrilla unit of the Justice Army "Yibyon" within the Righteous armies and the Korean Independence Army

The KPG set up training camps for independence fighters in China. The Korean Liberation Army fought operations along with British troops on the Indo-Burmese border. The most important independence activists spent time in China. Although we cannot cover the entire independence movement in this article, we will highlight a couple of very important people. The movie Harbin portrays An Jung Geun’s activities in China.

Korean independence activist Hong Beom-do relocated to Manchuria after the March 1 Movement. He led several key battles between resistance armies and Japan, including the Battle of Samdunja, (삼둔자 전투) the Battle of Fengwudong (also known as Battle of Bong Oh Dong, 봉오동 전투) and the Battle of Qingshanli (also known as Battle of Chung San Li, 청산리 전투), which led to the Gando Massacre. In 1921, Hong sought refuge in the Soviet Union, but Stalin disarmed the Korean troops. Hong’s entry document into Russia often gets remembered as an artifact that shows General Hong’s unwavering devotion to Korea’s independence. The Korean independence fighters refused to accept the Red Army and were surrounded and forced to disarm. The next year, Stalin annexed the area in Russia Far East where the Koreans were living. Hong’s remains returned to Korea in 2021.

General Hong’s Entry record into Russia in 1921 stating his job as “의병” (righteous army), and reason for entry “고려독립” Independence of Korea.

Independence activist Yun Bong-gil began as an independence activist in Korea, which brought him under surveillance. In the 1930s, after being arrested and briefly imprisoned, he moved to Manchuria to join the provisional government in Shanghai. He was the key activist involved in the Hongkou Park Incident in 1932 where, at a celebration for Emperor Hirohito in Shanghai, 10,000 Japanese troops were gathered. Top Japanese officers were on stage for the celebration when a bomb went off under the stage, killing a number of these key officers. Yun was arrested, with the help of the French, and executed by firing squad.

Independence activist Lee Bong-chang had moved to Japan in 1925 to work. He decided to go watch the crowning of Emperor Hirohito, but was arrested because he had a letter in his pocket written in Korean. The incident motivated him to join the resistance. He joined the KPG in Shanghai in 1930. In 1932, he attempted to assassinate Emperor Hirohito by throwing a grenade at him in Tokyo. This was later referred to as the Sakuradamon Incident. The attempt was unsuccessful and Lee was arrested and died in prison.

Koreans in Taiwan

Cho Myung Ha

Taiwan had been occupied by the Qing Dynasty before being ceded to Japan. Taiwanese attitudes towards Japan were not as negative as those of the Chinese and Koreans. Japan’s efforts to set up an orderly colony, industry, infrastructure and modernization in Taiwan shaped a more positive

Not a large number of Koreans were moved to Taiwan after Japan gained control in 1895. Some were conscripted as laborers, but Korean migration to Taiwan began largely after the March 1 Movement of March 1, 1919. Because of hardships caused by political crackdowns, Koreans seeking a better living migrated to Taiwan to work in the fishing industry, particularly to the port city of Keelung.

Independence activist Cho Myung-ha, who had been in Japan in 1926 to learn more about colonial power. He decided to join the Provisional Government of Korea (the resistance) in Shanghai and stopped over in Taiwan on the way. He heard General Kunihiko Kuninomiya, a Japanese general and a father-in-law of the Emperor of Japan, would visit Taiwan. He got a hold of a dagger and put poison on the blade. When the general visited, he attempted to kill him by throwing the dagger, but hit general’s driver in the back instead. Cho was tortured and executed for his act.

During WWII, Taiwan became a staging area for military operations by Japan in China and around the Pacific. Several thousand “Comfort Women” were brought to Taiwan for Japanese soldiers.

Koreans in Sakhalin

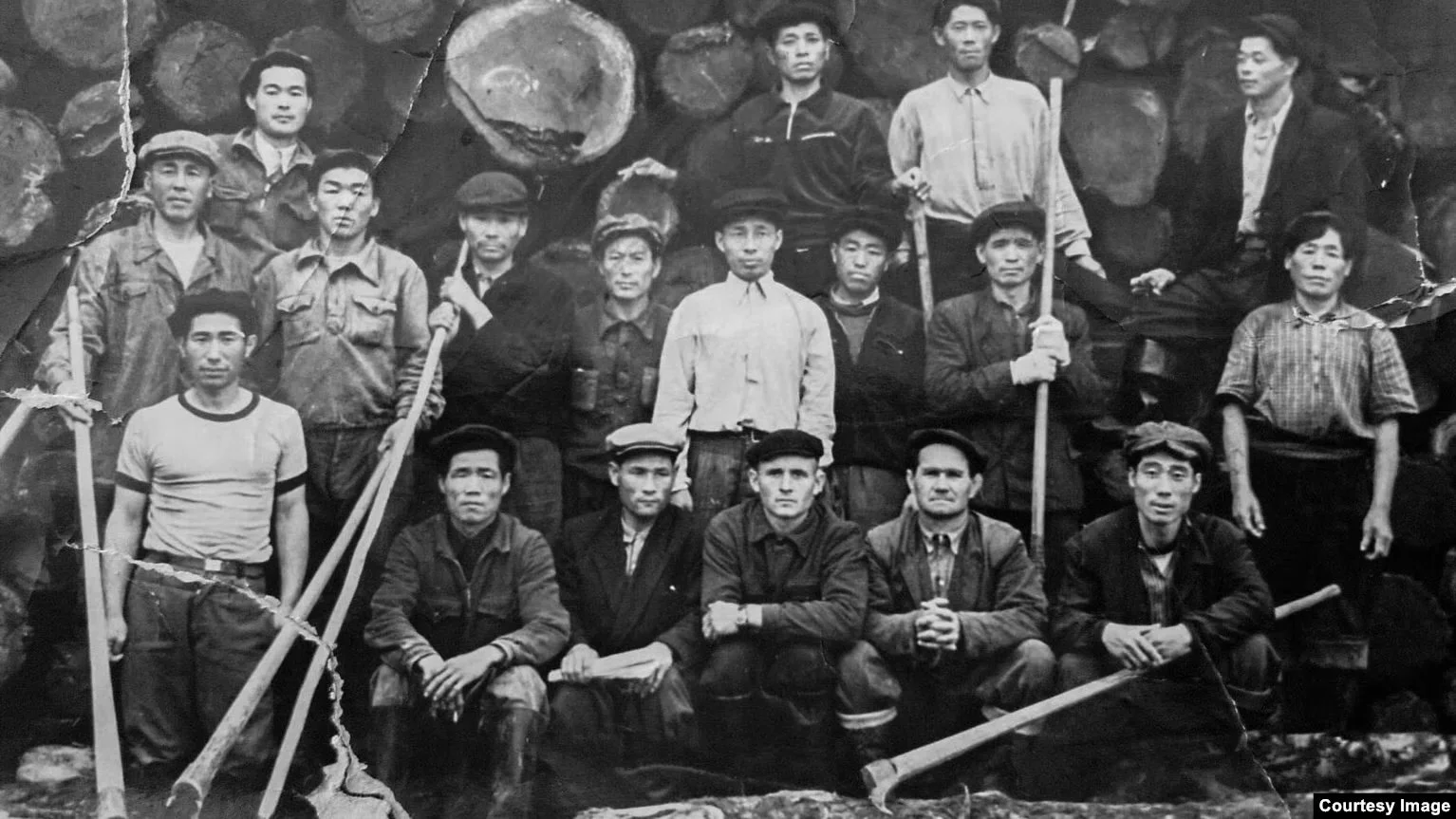

After occupation, Japan began bringing Koreans to Sakhalin (Karafuto Prefecture) to do heavy, difficult manual jobs such as mining, cutting lumber, creating paper pulp, creating roads and railways. Japan forced 150,000 Koreans to Sakhalin to work. The working conditions were horrible with many laborers dying.

Koreans in russia - Koryo-Saram or Koryo-in

(고려사람/ 고려인)

Deported Koreans from the Soviet Far East at a collective farm in Uzbek SSR (1937)

Migration to Russia by Koreans began in the late 1800s. As mentioned above, war, drought, famine and floods caused a number of Koreans to seek a new place to live and the farthest southeastern corner of Russia called Primorsky Krai had a population of 20% Koreans in 1869. The 1897 Russian census showed 26,005 Koreans living in Russia. After the Russo-Japanese war, an anti-Korean law was passed and land was confiscated from Koreans. Despite this, migration continued.

After the March 1 Movement in Korea, the city of Vladisvostok in Primorsky Krai housed a Korean neighborhood called Sinhanchon (New Korean Village) that was a center for the independence movement, including arms smuggling. The Japanese massacred hundreds of Koreans in Sinhanchon in 1920 as a result. By 1923, there were over 100,000 Koreans in Russia and by 1937, the number had grown to more than 168,000.

Believing that Japanese spies might have infiltrated the Korean population in Russia, Joseph Stalin ordered that the Koreans be deported from the Russian Far East to Central Asia, which today is Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. 124 trains moved 172,000 (100,000 to Kazakhstan and the rest to Uzbekistan) people 4,000 miles. Many faced starvation, freezing temperatures, unpotable water and lack of housing. An estimated 50,000 of the displaced Koreans died. Although Korean was taught as a second language until 1939, it was not taught at all at the end of WWII.

Koreans in Hawaii

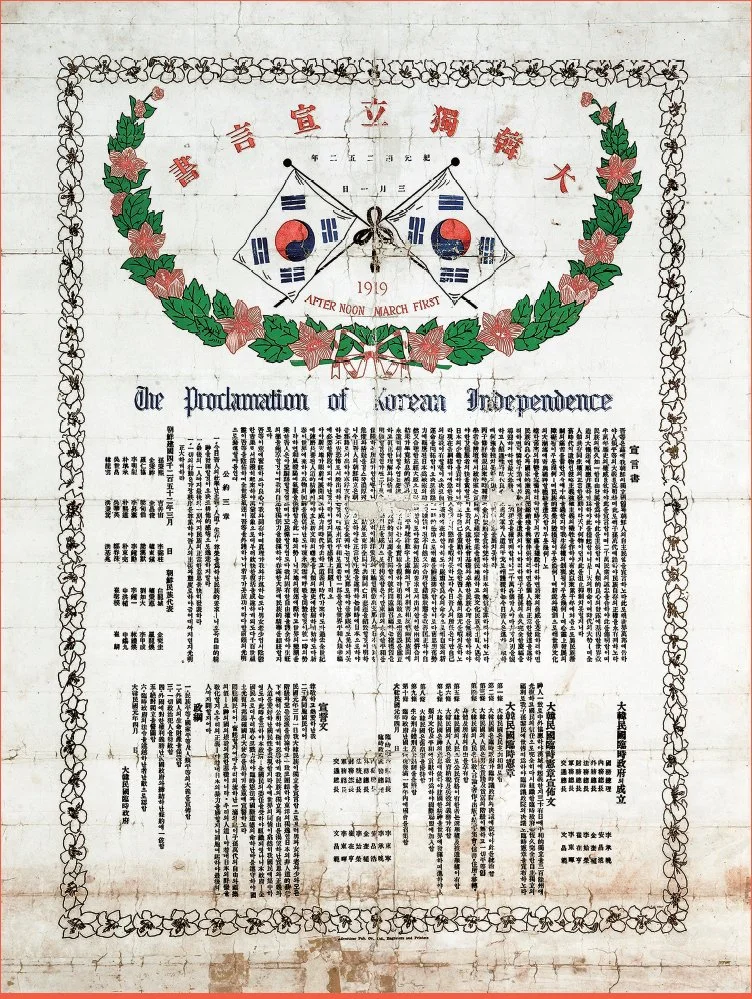

The Proclamation of Korean Independence (1919), Korean Women's Relief Society in Hawaii(1919~1945)

Koreans were contracted, mostly by American missionaries in Korea, to work in the sugar fields in Hawaii in the very early 1900s. By 1905, more than 7,000 Koreans were living in Hawaii. The monarchy in Hawaii had been overthrown in 1893 and this migration of Koreans was not legal, breaking U.S. migration laws. Many of this first wave of Koreans in Hawaii were looking to make a lot of money in the sugar plantations and return to Korea to settle and raise a family. The occupation of Japan in Korea changed those plans. Because the (mostly) men that had come to Hawaii could not return to Korea, Korean women were sent to Hawaii to marry the men. This was the second wave of Korean immigrants to Hawaii.

After the activist An Chung-geun killed a prominent Japanese official in China in 1909, the Hawaiian Korean community raised funds for his defense. The Koreans in Hawaii played a key role in the independence of Korea because the Koreans in Hawaii were the ones to gather funds for the March first Movement in 1919. An independence activist group made of Korean young females formed Daehan Girl’s League (대한소녀리그) to advocate for Korea’s independence by writing letters to the U.S. President Wilson and the U.S. representatives at the Paris Peace Conference. They were also active in the Korean National Association, which represented the interests of Koreans in the U.S., the Russia Far East and Manchuria. A number of prominent Korean independence activists spent time in Hawaii.

2,700 Koreans were held in internment camps in Hawaii with Japanese from 1943-1945. They were mostly civilians who had been forced to work with the Japanese and had been captured throughout the Pacific.

Koreans in Mérida, Mexico to Cuba

Koreans in Mexico: For the descendants of those first 1,033 travelers, that recognition is long overdue.

In the early 1900s, Mexico was experiencing labor shortages in agriculture. Natural disasters in Korea had displaced many people and many were looking for a better life somewhere else. Labor brokers from Mexico began advertising in Korea. In 1904, more than 1,000 Koreans departed on a British cargo ship from Incheon, despite efforts by the Korean government to stop them. They ended up in the Yucatan. They suffered not only from harsh treatment and endless working hours, but from many gastrointestinal issues due to a complete change in diet. A number of them died.

They had a four-year contract, but they had to pay their own return fare and after four years, most had not saved enough to be able to return. Add to this the fact that Korea had become a protectorate of Japan and effectively not a free country. Japan didn’t advocate for them. Korea had no power to send for them. The Mexican government didn’t advocate for them. They were essentially stateless. The organization of Dosan in San Francisco tried to arrange for them to go to Hawaii, but those plans did not work out. After the collapse of the agave industry in Mexico in 1921, a large number of them went to Cuba, the rest remaining in Mexico. Instead of finding a better life in Cuba, they were sold to landowners and ended up working in the fields under brutal conditions. A feture documentary on Cuban Korean Jeronimo (2019) is available on Tubi.

Post-War Migration

North Korean prisoners of war migrated to Chile in 1953 and Argentina in 1956 under the auspices of the International Red Cross.

Post WWII Diaspora

China

Many Koreans living in China returned to Korea to fight in the Korean War, mostly fighting for the North.

In 1952 the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture was established where so many Koreans had migrated since the mid-1800s. It was one of 157 autonomous areas set up by the Republic of China for ethnic minorities. Many Yanbian Koreans died during the Korean War, but the majority of ethnic Koreans still living in China reside in the Yanbian area. Chaoxianzu style Korean is spoken here, which is also known as Chinese Korean and is a Korean dialect related to the North Korean dialect.

The other post-war concentration of Koreans in China is found in the Changbai Korean Autonomous County, which is located on the border with North Korea and has a population of 75,000+. Chinese Korean is also spoken in this region.

Taiwanese Koreans

At the end of the war, about 3,500 Koreans were in Taiwan. All but about 400 Koreans left Taiwan and repatriated to Korea. The majority of those that stayed were working in the fishing industry in Keelung and had good jobs, as well as being provided housing. Some Koreans that stayed were “Comfort Women” who either had no family or no family that would accept them back in Korea. About 50 of these women had been sent from Taiwan to Borneo. A few “Comfort Women” were able to marry Taiwanese men and therefore remain.

Sakhalin Koreans

Russia invaded Sakhalin in August of 1945, three days before the surrender of Japan. 100,000 Japanese and Koreans managed to escape to Hokkaido. It isn’t clear exactly how many Koreans died on Sakhalin, but many did. Of those that were left, roughly 45,000 were Korean. The Russians repatriated the Japanese, but refused to let the Koreans leave. They needed labor on the island and considered the Koreans stateless after the war in addition to the growing conflict between the Soviet Union and the U.S. over the peninsula of Korea. The Russians basically reconscripted them to heavy labor. Japan also refused to accept them. After the Korean War, the Soviet Union’s attitude hardened, because most of the Sakhalin Koreans had come from South Korea.

By the 1960s, around 25,000 of the stranded Koreans had decided to repatriate to North Korea, which the Soviet Union allowed. Another 12,000 chose Russian citizenship, though they experienced life as second-class citizens. The remaining Koreans still sought repatriation to South Korea and remained stateless, making their lives very difficult. By 1985, the community of stateless Sakhalin Koreans numbered around 10,000. As the Soviet Union collapsed a few years later, Sakhalin Koreans felt more comfortable because they were allowed to learn and study in Korean again and the younger generation has mostly melded into Russian society. Japan finally agreed to pay to repatriate the first-generation Koreans remaining on the island that still wanted to go home. The repatriation happened in waves and continues through the early 2000s. 100 just returned in February of 2025.

Russian Koreans - Koryo-Saram or Kore-Saram

In 1947, the Koreans that had been banished to Central Asia were allowed to obtain Russian passports, but they could not travel outside of the Central Asian region. In general, they were not allowed to repatriate to Korea. A few went to North Korea after the division of the peninsula, however Kim Il Sung purged the Soviet-connected Koreans in the 1950s and many of them returned to Central Asia. Elsewhere in the newsletter, we hear the history of Sergey’s family, who are Koryo-Saram.

The forced banishment of the Koryo-Saram isolated them from their roots, their language and their culture. Generationally, Koryo-Saram have lost their ability to speak Korean. There was no effort by South Korea to repatriate the diaspora in Central Asia. They have, however, set up programs to promote the language and culture within Central Asia. In the 1950s and 1960s, some Koryo-Saram migrated elsewhere within Central Asia.

Denis Ten, Kazakhstan’s Olympic Bronze Medalist in Figure Skating

To this day, about 500,000 Koryo-Saram are spread over Russia and Soviet Union countries. Unfortunately, about 10 percent of the population are considered stateless as many of Koryo-sarams were not aware of the fact that they had to register their citizenship after the USSR dissolved or because they did not have the financial resources to do so.. The stateless Koryo-sarams face discrimination and many difficulties as no government recognizes their citizenship. The government of South Korea is currently helping some Koryo-sarams to recover their citizenship and migrate back to mainland Korea.

Viktor Tsoi, one of the most influential musicians of the Soviet Union, was a descendant of a Koryo-saram. Born to a Russian mother and Koryo-Saram, Tsoi left significant footprints in Russian popular music. Unfortunately, he died in a traffic accident, but his life was portrayed in the movie Leto.

Denis Ten, Kazakhstan’s first ever Olympic medalist was also a Koryo-saram. He was a bronze medalist in men’s figure skating. He was murdered at age 25, but he is still remembered by many people. Denist Ten was a descendent of Independence activist Min Geung Ho who was killed in 1908. When Min died, An Jung Geun helped the family to cross borders into Russia.

Hawaii

Because of the alliance between the U.S. and the southern part of Korea post-WWII and then the subsequent war in Korea, immigration to Hawaii after the war increased greatly. Many Koreans were looking for a more stable life and many came in as brides of servicemen.

Mérida, Mexico

Descendants of the first agricultural migrants from Korea to Mexico now number approximately 400,000. Since these Koreans could not return to Korea, their stories continue in Mexico. In 2007, the South Korean government built a museum, statue and hospital for the community in Mérida.

Japan

Ethnic Koreans who originated from Korea and are living in Japan are known as Zainichi. They make up the third largest ethnic minority in Japan.

After the war, most Koreans wanted to repatriate to Korea. Some Koreans could not speak Korean and Korean schools were set up in Japan to prepare them to return. These schools were closed quickly in 1948 because of details in the Treaty of San Francisco, trying to re-establish Japan’s sovereignty. In 1947, 1.4 million Koreans returned to South Korea. But many had difficulty deciding which half of Korea to repatriate to. They had to choose to be North Korean, South Korean or Japanese. If they did not choose, they became stateless. After 1950, South Korea no longer accepted Koreans that wanted to repatriate from Japan. However, North Korea continued accepting people through the 1980s. There are still almost 25,000 stateless people that originated from Korea in Japan.

Both Koreans that stayed and those that repatriated have had to live with the effects of radiation from the atomic bomb blasts.

Other Locations

After the Korean War, North Korean prisoners of war migrated to Chile in 1953 and Argentina in 1956 under the auspices of the International Red Cross. Koreans connected to textile industries formed large Koreatowns in Brazil and Guatemala over the subsequent years.

Our community knows very well the history of the post-Korean War adoption of children to the U.S. and Europe. We represent the community every month in this newsletter.

Reverse Migration and Repatriation After Death

There has been a trend in recent years for members of the Korean diaspora to return to South Korea. Many factors, including cost of living, health care, safety are factoring into ethnic Korean’s decision to return to live in South Korea.

Members of the Korean diaspora who are direct descendants of pre-1945 Koreans can apply to be buried in Korea after their death. National Mang-Hyang Cemetery in the Cheonan district is a central location for the burial of the Korean diaspora.

Further reading:

Pre-WWII history:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ming_dynasty#Fall_of_the_Ming

Occupation history:

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1398/the-japanese-invasion-of-korea-1592-8-ce/

https://accesson.kr/rks/assets/pdf/7601/journal-10-2-161.pdf

General Migration History:

https://openkorea.org/history/the-journey-of-korean-immigrants-outside-the-united-states/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russian_Far_East#Russo-Japanese_War

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koreans_in_China#Early_history

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0169809523005173#preview-section-snippets

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koreans_in_Mexico#Early_20th_century

Koreans in Japan:

https://seedswillgrow.com/2025/06/24/untold-story-of-koreans-in-japan/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14672715.1991.10413161

Koreans in China and Independence Movement:

https://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/History/Independence-Movement

http://www.asianinfo.org/asianinfo/korea/history/independence_army.htm

https://militarylookbook.blogspot.com/2023/05/the-life-and-achievements-of-korean.html

https://world.kbs.co.kr/service/contents_view.htm?menu_cate=history&board_seq=61201&page=18

Taiwanese Koreans:

https://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Taiwan/sub5_1a/entry-3796.html

https://iccs.chss.nycu.edu.tw/en/wps_one.php?USN=43

Sakhalin Koreans:

https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-sakhalin-koreans-japan-forced-labor-repatriation/32798117.html

https://tucson.com/news/national/article_81a144e4-6a4e-54dc-9dfc-ff1f0973804e.html

https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Society/view?articleId=266173

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sakhalin_Koreans#

Russian Koreans:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Koryo-saram#Immigration_to_the_Russian_Far_East_and_Siberia