THIS MONTH IN KOREAN HISTORY - Feb 2026

Daegu Subway Fire

By Sharon Stern

On February 18, 2003, an arsonist struck a train in Daegu. This tragedy is one of at least three in recent Korean history that has strongly shaped public sentiment and caused widespread anger over the enormous loss of lives, the errors of those in charge at the scenes and the poor or slow governmental responses. The other two tragedies were the Sewol Ferry disaster in 2014 and the Itaewon Halloween Crush in 2022.

These disasters had followed a several disasters in the 1990s, really just after South Korean independence from dictatorial rule, including the 1994 Seongsu Bride collapse that killed 32, the 1995 collapse of the Sampoon Department Store that killed 502 and the 1995 gas main explosion in Daegu during subway construction that killed 101. All of these 1990s disasters were attributed to corporate greed being placed over public safety.

We have usually concentrated on older moments in Korean history, but it is important to also understand the events shaping modern South Korea.

Daegu

Daegu Metropolitan City, North Gyeongsang Province, South Korea.

Daegu is a city in Southeastern South Korea. Daegu has been a center for transportation and trade from before written history. Two rivers converge in Daegu: the Geumho (금호강) and the Nakong (낙동강), which is the longest river in South Korea and also runs through Busan. Daegu also lays on what was the Great Yeongnam Road (영남대로), which was a major road during the Joseon Dynasty between Hanseong (modern day Seoul) and Dongnae (modern day Busan). The route maintained its significance when the Gyeongbu Line railroad was built in 1905 along the same path. Daegu was an important center during the Korean War because many heavy battles were fought along the Nakong River. It is ironic, then, that one of the worst transportation disasters in modern Korean history took place in Daegu. As we will see, significant, good changes took place as a result of the disaster, but that is little concession to the families of those who lost lives.

The Arsonist

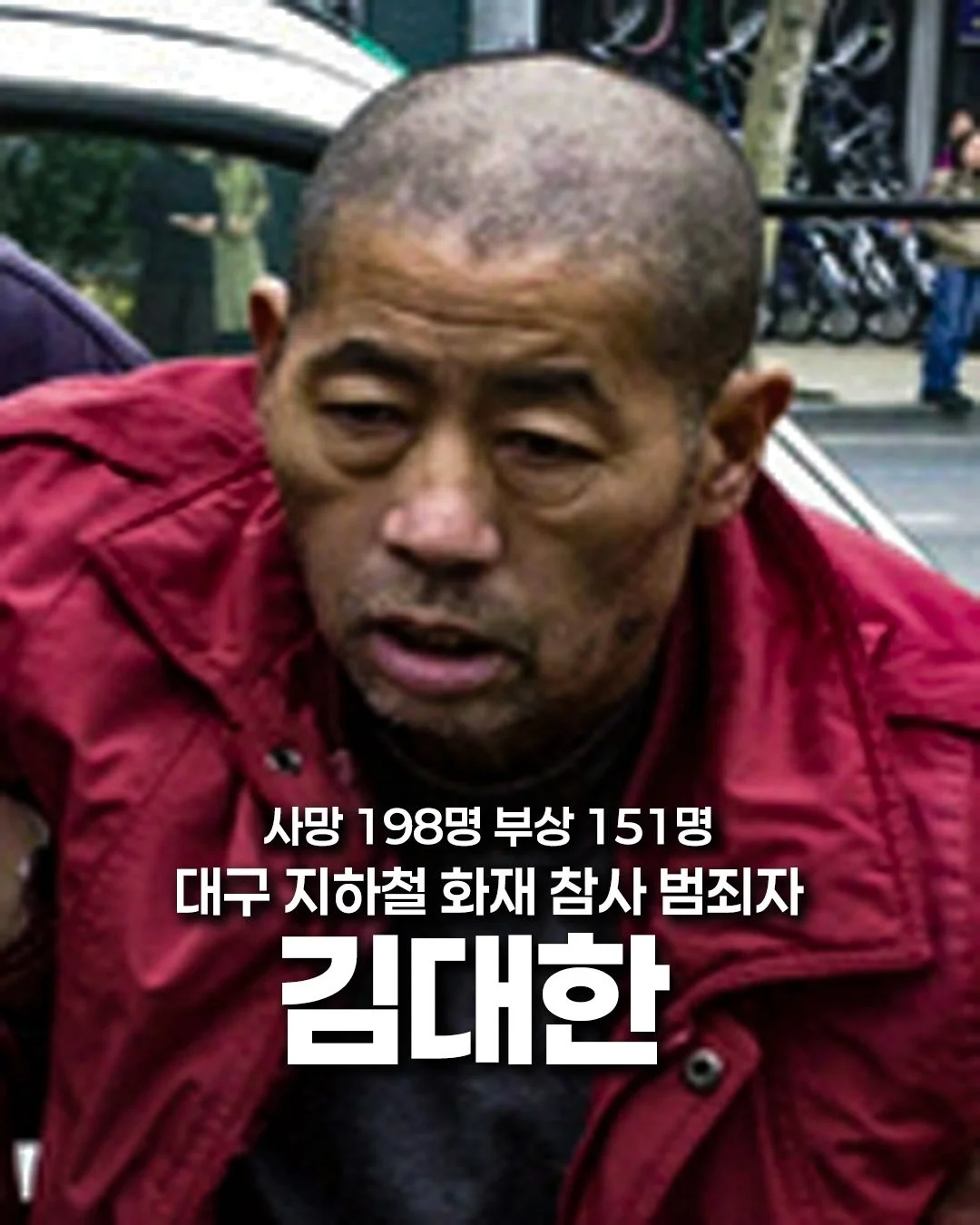

Kim Dae Han, the arsonist of the Daegu Subway Fire. The photo notes 198 death and 151 injured. Kim died in prison in 2004.

Kim Dae-han was 56 years old and unemployed. He had been a truck driver, a taxi driver, and then a street worker, but had had a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and caused him to lose his job. He was depressed and had been diagnosed as such, frustrated with his medical treatment and was having violent thoughts. After the incident, he told police that he wanted to die, but he wanted to do so in a crowded place and take others with him.

At 9:53 am on the morning of February 18, 2003, he got onto the 1079 train on Line 1 in Banwoldang Station in Daeksandong, near downtown Daegu. He was carrying a duffle bag with a four-liter milk jug filled with a flammable liquid – probably gasoline.

After the train left the station, Kim Dae-han sat in the seats reserved for elderly and handicapped riders and began fumbling with the milk jug and a lighter. Other passengers had noted that he was acting suspiciously as soon as he boarded the train. They started yelling at him to stop and he repeatedly mumbled “I’m going to die.” As the train pulled into Jungangno Station, the central station of downtown Daegu, a scuffle broke out with other passengers trying to stop him from lighting a fire. The milk jug fell and spilled the flammable liquid and he ignited the fire..

The Incident

Train 1079 is currently preserved at Daegu Safety Theme Park. Photo Credit: Sung Dong Hoon/ Kyunghang

Kim Dae-han’s back and legs were on fire, but he and many of the passengers of the train were able to escape. Because the train was in the station, its doors were open. However, the fire very, very quickly spread to all six cars of the train. The seats, the flooring, the hand straps, the advertising boards, the insulation and even the materials making up the interior walls of the train cars were all flammable – made of fiberglass, carbonated vinyl and polyethylene. They all produced very heavy, toxic smoke along with the flames. There were 200 passengers on board train 1079.

The subway driver didn’t call in the incident right away to the control center and brought a fire extinguisher to try to put out the fire. The official procedure was to call the control center first and then try to put out the fire. He didn’t do that. The fire was already too intense and the fire extinguisher couldn’t do much. He told the remaining passengers to evacuate, which they mostly did, though passengers in the furthest cars did not get this message.

The station control center that watched CCTV of the rails and station saw smoke and told the driver of train 1080, traveling in the opposite direction and approaching the station, to proceed into the station with caution because they could see smoke. The fire alarms were sounding, but the control center still didn’t know the nature or size of the fire because they had not communicated with the train conductor. The station’s control center did not call the fire department, because they did not have details about the fire. However, a passenger that had escaped, got outside of the train station and did call the fire department.

When train 1080 pulled into the station, it stopped parallel to train 1079 that was already on fire. The driver opened the doors, but there was so much smoke pouring in that he immediately closed the doors. He called the control center and said that there was too much smoke in the station. Shortly thereafter, an automatic fire detection system shut down the power to both trains, meaning that train 1080 could not leave the station, even if they had wanted to.

Portraits of the victims.

Three separate times, the driver of train 1080 told his passengers to remain seated on the train while he was trying to communicate with the control center and find out what was going on and how he should respond. They sat in the train cars, breathing in toxic smoke for six minutes. He was finally advised by the control center to quickly leave and get out. When he went to leave, he took the master key for the train, which was the documented procedure, but which cut power from the backup batteries on board the train to any of the mechanics on the train, meaning that the doors of the train were locked shut. There were 250 passengers on board train 1080.

Before the driver pulled the master key, 171 passengers were able to escape. However, all 79 that were locked in the train passed away from asphyxiation. There were still 70 passengers on board train cars on train 1079. All of them died as well. Many messaged loved ones as they were dying, knowing very well what was going to happen. In addition to the 149 train passengers that died, another 43 people died from asphyxiation, 151 were injured and 60 people were unaccounted for in the immediate chaos that ensued. Most of the victims were students heading to school. The incident occurred during rush hour.

The fire burned so hot because of all of the flammable materials that its intensity reached 1000°C on both trains. 84 fire trucks and 1,300 people responded to the disaster. The fire burned most intensely for only 20 minutes, but it took three hours to take control of the station because of the toxic smoke.

The interior of one of the subway trains destroyed in the Daegu metro fire, as seen in this undated file photo (Yonhap)

The train was not equipped with readily available fire extinguishers. The windows did not open. There was an emergency door opening level, but it located underneath a seat near the doors, not well labeled and passengers wouldn’t have known where to find it in the smokey environment. There were fire extinguishers, but they were inside of unmarked cabinets at the end of the train cars. There was no button or call system to communicate with the driver or the station. The station did not have sprinklers on the third level where the fire took place. There was a lack of emergency lighting, which confused those passengers that did exit the trains and these were among the additional dead, since they couldn’t find the stairs to exit the station. All 12 subway cars – six on each train – were completely destroyed. All of the signage and the floor of the train station were destroyed. The fire was so hot that the roof of the station above the trains was damaged to expose the interior steel reinforcement. Several victims could not be identified by DNA because their bodies were so completely burned that it wasn’t possible. DNA identification was necessary to identify other victims because they were not recognizable.

Aftermath

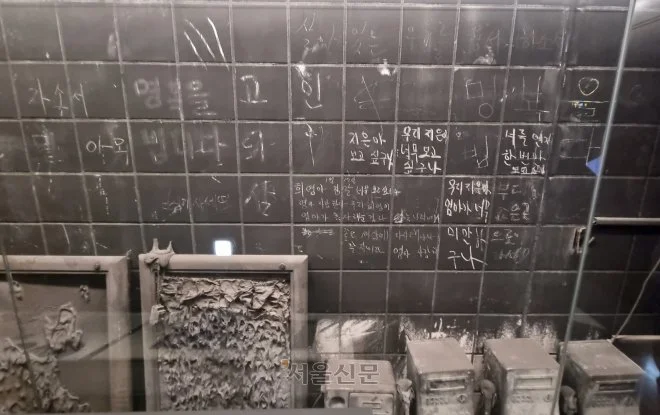

Messages written on the burnt walls of the subway station by the surviving relatives of victims.

Relatives of the victims became increasingly angry as the process to identify victims dragged on. Because of the intensity of the fire, identification was difficult and physical identification was impossible. The process was, indeed, slow, but relatives were overwrought and anxious.

Kim Dae-han fled the station and went to a hospital, where he was quickly arrested. The conductor of train 1080 also fled and wasn’t found until ten hours later. During those ten hours, he apparently colluded with Daegu Metropolitan Subway Corporation bosses to delete, change and hide information. Both train conductors were arrested. Seven employees in the station’s control center were also arrested. There was an attempt to cover up evidence before it was handed to police and for that reason as well as the poor response by train employees and the lack of safety equipment available, the head of the Daegu Metropolitan Subway Corporation was fired. Kim Dae-han was sentenced to life in prison, though families of the victims called for the death penalty. He died just a year later in prison of chronic disease, no doubt exacerbated by toxic smoke inhalation. The two conductors received four and five year sentences. The control center operators received between two and five year sentences.

The train station was repaired and reopened four years later. Six other stations had to be closed temporarily to clean the smoke damage. In 2015, after years of internal conflicts between different organizations, including victim’s families, a memorial area was opened in the Jungangno Station, containing melted pieces of subway car, part of the station wall, an ATM machine and other artifacts. A wall of the fire site was preserved. Sadly, there are messages scratched into the thick, black smoke covering the pieces of subway cars, etched by the victims as they were dying. And photos of the victims line the memorial wall as well.

This disaster happened in the middle of a presidential transition. President Kim Dae-jung ended his presidency on February 24, 2003 and President Roh Moo-hyun took over. President Roh was immediately confronted by victim’s families. It wasn’t a good start for what would be a controversial presidency.

Memorial Hall for 2.18 Daegu Subway Fire. Photo Credit: Daegu Jung-gu instagram.

In 2008, a kind of theme park opened in Daegu called the Daegu Safety Theme Park. One of the burnt subway cars from the fire is on display there. The idea of the theme park is to teach everyone how to safely evacuate from a subway fire, but it has been expanded to include CPR training, earthquake preparedness, traffic safety, among other subjects. A visit to the theme park will show you a movie about the disaster and take you through a physical experience of escaping from a subway car and safely exiting the subway station in the middle of a disaster, (safe) smoke included. Testimony of visitors say that the experience is extremely intense. Their website has a virtual tour and even that is a little intense.

The government did pay restitution to families of victims and surviving victims. They helped pay medical expenses for the injured. But much more money was privately donated to help survivors and victim’s families. Survivors suffered from a very high rate of PTSD, even many years after the disaster. On the 20th anniversary, victim’s families and survivors gathered for a memorial service, but local merchants staged a protest and the mayor of Daegu did not attend. Because victim’s families of both the Sewol and Incheon disasters were also present, they complained that the memorial had been politicized and would negatively impact local sales.

Reforms

Firefighter inspecting the 5 train of Seoul Metro, which was set on fire in 2025. Despite the fire, the train was not destroyeed, and there were no death because all the seats were replaced with inflammable material after the Daegu Subway Fire.

In January of 2004, South Korea established a Fire and Disaster Prevention Agency. In March of 2004 the Basic Law on Disaster and Safety Management was passed and a series of safety measures for subways was slowly put into place. It happened slowly because of costs, but the initial requirement was to retrofit subway stations and trains with more safety materials and procedures by 2005.

Even if the reforms were slower than everyone might have wanted, the reforms that have been implemented are stricter, more robust and universally applied than for any mass transit system in any other country. That is something for South Korea to be proud of.

In 2005, Daegu Metropolitan Government published a whitepaper about the disaster, pointing a finger at the flammable materials that allowed the fire to spread so rapidly. The materials used were light weight and cheap, but by 2009 all flammable materials in subway cars had been replaced, most replaced with steel. This reform was tested in 2014, when a 71-year-old man tried to start a fire in a subway car in Seoul, but it was easily contained within 10 minutes and put out. Specifically detailed safety manuals for train operators and station personnel have been written and put into use since the disaster. Regular fire response drills are enacted every three to four months.

Flammable materials have also been removed from train platforms and surrounding areas. 13,000 new sprinklers and fire detectors were installed in the Daegu system alone. Emergency lighting and flashlights have been installed in train stations.

In 2005, any facility that could house 100 people had to have self-contained breathing apparatuses (gas masks) to use in case of emergencies. Manual door levers are now larger and brightly colored, with posted instructions. Flash lights and fire extinguishers are readily available and marked both on the trains and in the stations. Communication systems have been added so that passengers can communicate via intercom with both conductors and the control center. Wireless systems were installed so that conductors can more easily communicate with control centers. Automatically deploying fire doors are present in subway stations to limit smoke distribution. New ventilation systems were installed in train stations.

It is now illegal to sell gasoline that will be placed in a non-gasoline container, such as a milk or juice bottle. It is also illegal to transport hazardous materials on trains and busses.

It is unfortunate that it often takes a disaster in order for reforms to be implemented, but the Daegu Subway Fire has made mass transportation in South Korea some of the safest in the world.

Further Reading

https://www.koreaherald.com/article/3231020

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daegu_subway_fire

https://www.blueroofpolitics.com/post/twenty-years-on-no-closure-in-the-daegu-subway-disaster/

https://railsystem.net/south-korea-daegu-subway-station-arson/

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2780061.stm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2779393.stm

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/southkorea/20160218/victims-families-remember-deadly-daegu-subway-fire

https://goughlui.com/2020/01/05/opinion-daegu-2003-2-18-subway-fire-memorial-aftermath/

https://kstationtv.com/2023/12/13/ksis-the-devastating-fire-of-the-daegu-subway/?lang=en

http://koreabizwire.com/memorial-space-created-at-daegu-subway-fire-site/47459

https://publications.iafss.org/publications/aofst/6/s-5/view/aofst_6.pdf

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/february-18/arsonist-sets-fire-in-south-korean-subway