THIS MONTH IN KOREAN HISTORY - Dec 2025

The Imjin War of 1592-1598

By Sharon Stern

This month we are covering some details about the Imjin War (also known as the Seven Year War) that took place between 1592 and 1598. The final battle took place on December 16 with the final Japanese ships leaving Korea on December 24, so it is appropriate to focus on this month. The name “Imjin” comes from the name of the year 1592 in the originally Chinese sexagenary (60 year) cycle that had a unique name for each year in the cycle.

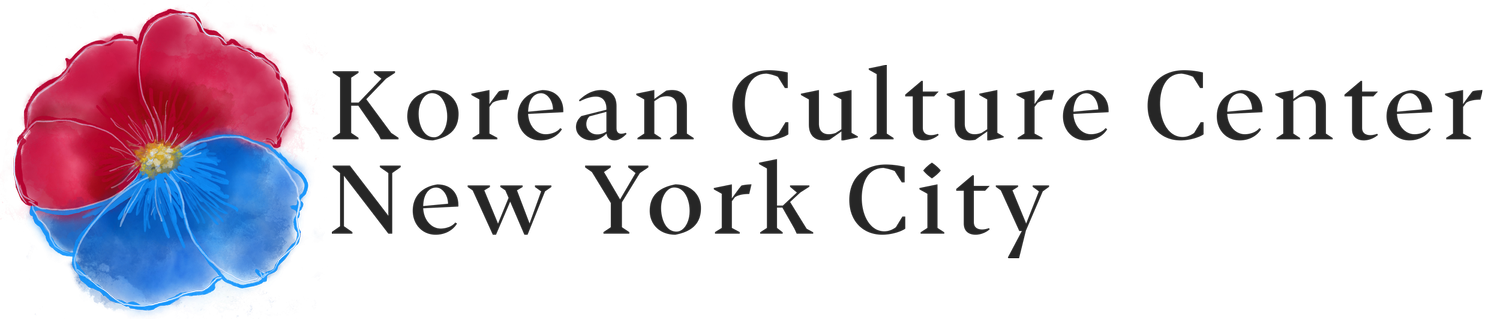

Korean and Chinese forces attacking the Japanese Fort of Ulsan (Municipal Museum of Fukuoka, Japan)

History can sometimes seem boring, but the Imjin War had significant consequences for Korea, China and Japan. The loss of life, arable land, cultural and historical records, artifacts and sites and the capture and forced transfer of tens of thousands of Koreans to Japan created devastation for Korea that was more significant even than the Korean War. The conflict with Japan set the tone, context and platform for tensions that have lasted several hundred years and persist today. This was the only military conflict involving Korean, China and Japan between 1281 and 1894. It seems like such a long time ago, but understanding this history helps us understand aspects of all three country’s present-day attitudes and values.

By the end of the war, Japan suffered an estimated 150,000 military deaths (1/2 of the army), Ming China lost another 300,000 and Korea lost an estimated 260,000 military personnel and another million civilians. The losses are pretty mind boggling. We will look at the losses for China and Japan, but the losses for Korea cannot be understated. One of the most significant losses was in the cultural appropriation of potters, pottery-making skills and knowledge by the Japanese. If you don’t read any other part of this article, skip down and read about this – it is one of the most profound and lasting impacts of this war.

The Beginnings

"Toyotomi Hideyoshi portrait" (1598), Kōdai-ji Temple, Kyoto.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was a Japanese samurai (members of the warrior class that supported the war lords) and daimyo (feudal war lord) and was considered the second Great Unifier of Japan. He was given the title Kampaku, which was essentially a chief advisor to the emperor. He was the most powerful military leader in Japan, after the death of Oda Nobunanga, who he served under. From 1585-1592 he led forces that conquered many of the provinces, castles (important defensive forts established by clans) and territories of powerful clans, concentrating power under his forces and therefore creating a unified state.

In 1587, he tried to establish diplomatic relations with Korea, which had been broken off thirty years prior. He hoped that he could ally with Korea to conquer Ming China. In 1592, he intended to take over the Ming Dynasty in China by first passing through and taking over Korea.

It is important to understand that at this time Korea was relatively stable, but suffered from internal clan conflicts. In 1401, Korea had become a tributary state, though the highest ranking tributary state, of the Ming Dynasty. Korea considered China the center of the Confucian universe and Korea’s role was that of a lesser and subservient state to Ming. In addition, Korea, having relaxed because of a couple hundred years without conflict, did not have a large, centralized or well-organized army. The navy existed pretty much entirely to ward off Waegu pirates and secure shipping lanes. Korea’s weaponry was technologically inferior to Japan’s, though still impressive (we will explore this below), but this left Korea vulnerable to Japan’s highly organized attack.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi had intentions of creating an empire that included China, Korea, the Philippines, India, islands in the South China Sea as well as other tributary states of the Ming. That takeover of China, and in the process Korea, was going to be just a first step of his empire building.

Dongnaeupseong Fortress in current day Busan

On April 13, 1592, 700 ships carrying 18,700 Japanese troops entered Korean waters. On May 23, 1592, 7,000 Japanese soldiers came to Busan. The Korean naval intelligence at first misidentified them as trade ships. After landing, the Japanese asked Korea for safe passage to China. They refused, as they had in the past. This time, however, the Japanese attacked Busan. This was the real beginning of the six-year conflict.

The initial attack destroyed much of the Dongnaeeupseong (Dongnaeeup Fortress) near Busan that had existed since the Goryeo era. It was left mostly in ruins until the late 1731 when it was rebuilt and a town was established inside of the fortress walls. More work was done to fortify the location in the 1870s, when a presumed new invasion by Japan was expected. It is now a popular tourist site.

Drawing of the Battle of Dongnae Fortress (1658)

During this initial attack, Toyotomi Hideyoshi sent a message to the commander of the fortress, saying that he would spare lives if he was given safe passage towards China. The commander responded by saying, “It is easy for me to die, but difficult to let you pass,” and Hideyoshi gave orders to spare no lives of any kind and take no prisoners. Every living thing, including cats and dogs and plants, were killed and agricultural land was burned. The Koreans sent envoys to Beijing to ask for military help. The Chinese said they would send help, but they were already involved in battles with the Mongols, including what became an internal rebellion allied with the Mongols and the Koreans had to wait for assistance

By June, the Japanese were able to cross the Imjin River (downstream of the Han) into Hanseong (now Seoul) and there was a large slaughter of Korean army personnel in the battle to keep them out. King Seonjo and palace officials fled to Pyongyang, leaving commander General Kim Myeong-won to defend Hanseong. The Korean troops ended up retreating to Kaesong Fortress (in current North Korea). By the end of the July, Japanese troops had reached all the way into Pyongyang and into Manchuria. As they advanced, the Japanese captured strategic fortresses in each province. The Ming finally, after consulting with Koreans in the area of Pyongyang and after their decided victories against the Mongols in China that had been delaying them, sent troops into Korea in August and September.

Because the 1592 initial attack was a surprise, it didn’t meet with much resistance. This was true both on land, but also at sea.

The Korean navy quickly regrouped, however. There are only a couple of names from this period that you should know well. One of them is Admiral Yi Sun-sin. As the Japanese pushed towards Hanseong and to Pyongyang, their supplies were coming from the coast. In four decisive naval battles during the 1592 invasion, Admiral Yi and his compatriot Admiral Yi Eok-gi and later also Admiral Won Kyun, successfully surrounded and destroyed over 200 Japanese ships and captured many more.

Rebuilt replica of the Admiral Yi’s turtle ship based on historical records. However, disputes about the accuracy of the replicated model remain.

The first naval battles included mostly fishing boats, but by the last battle of 1592, Admiral Yi had debuted the now infamous turtle ship or gwiseon (귀선) and had between five and eight in use. Admiral Yi’s genius was not uniquely in the design of ships, but in his prowess in war strategy. His battle plans have been studied for centuries. Admiral Yi’s diaries survived and the details outline his strategic thinking.

The turtle ship was completely clad in spiked iron. The cladding protected the ship from attacks, boarding, but also fire. In addition, the ship had 36 canons and holes between a separate layer of cladding where soldiers could aim arrows to fire at the enemy, if they attempted to board. The turtle ships helped the Korean navy cut off supply lines to the Japanese, making their invasion much more difficult.

1593-1597 – Righteous Armies and Warrior Monks

Current day Hengjusanseong, Gyeonggi-do, Korea. Photo Credit: Gyeonggi Provincial Office

In February, 1593, 43,000 Chinese, 10,000 Koreans in addition to Righteous Army guerrillas and about 5,000 warrior monks retook Pyongyang. Soon after, troops retook Kaesong. The Japanese tried to take Haengjusanseong (Haengjusan Fortress) in the mountains to the south of what is now Seoul, but a few thousand Korean troops, some clever weapons and the help of local residents helped push back Japan’s 30,000 troops. Without supplies and with great losses, the Japanese had to retreat back to the coast. To this day, the battle at Haengjusanseong, known as the Battle of Haengju, is celebrated as one of the most decisive Korean victories of the war.

After the initial attacks in 1592, Korea reorganized its military training and increased the size of its army. But there were two groups of non-military militias that spontaneously formed and helped Korea gain victories and ultimately the final victory of the war. The first of these were the Righteous Armies. The Righteous Armies would come into play a second time during the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910-1945, where civilian militias played an important part in resistance to the occupation. The Righteous Armies included scholars, former government officials and peasants. They were led by the Seonbi class, generally non-governmental public servants who were educated and were believed necessary to lead the common class in the ways of righteous living. They were not well armed, nor well trained, but they were passionate. The Japanese did not expect organized, civilian resistance and the Righteous Armies were key to Korea winning the battles that they did.

Portrait of Seosan Daesa (Cheongheodang, 1520–1604)

Along side the Righteous Armies were groups of warrior monks. Readers might be familiar with the Shaolin monks of China through kung fu movies. The warrior monks of Korea were similar in many ways. They studied and practiced a unique kind of martial arts simultaneously with their studies of Buddhist philosophy. Two monks in particular, Hyujeong (also called Seosan Daesa) and Yeonggyu, were responsible for responsible for the formation of the warrior monk groups that joined the Righteous Armies to fight. It wasn’t until the Kabo Reforms in 1894 that the warrior monk armies were disbanded.

Various large battles ensued in the next 12-18 months. In the spring of 1594, Chinese commandos were able to enter Hanseong and burn Japanese supplies. By May, most of the Japanese had retreated back to Busan. For the next three years, there were few battles and the Japanese maintained their position around Busan. Negotiations for a permanent truce were on-going between the Ming and the Japanese, but both sides believed that they would be left in control of each other and the negotiations didn’t go anywhere. During this time, Japan withdrew most of its troops from Korea and the Ming withdrew all of theirs.

Inter-war Reorganization

A model of Hwacha displayed in Seoul War Memorial.

In the time between the invasions of 1592 and the second invasion in 1597, Korea assessed its military weaknesses and issues. The army was reorganized and advised by Ming commanders and a form of inscription was put into place to assure reserve levels of soldiers were available. The Military Training Agency was established and formal training camps were created.

At the same time, Admiral Yi built as many turtle ships as he could, in addition to more panokseons (판옥선), a type of both oar and sail propelled war ship that carried canons.

Some of the weapons the Koreans and the Ming used helped in their final victories. The period of reorganization helped them build and accumulate more of these. One of the most famous is the hwacha (화차) or fire cart. This was a type of rolling, wooden cart loaded with 200 arrows propelled by gunpowder. They actually look very similar to modern barrage rockets, but using arrows instead of rockets. This weapon has been so legendary through time that the TV program MythBusters took on the challenge of seeing how it worked in action. You can see the video here. This weapon surprised the Japanese and was very lethal.

Chongyu War: Second Invasion (1597–1598)

Ear Mound in Kyoto, ears and noses of Joseon people were buried in these graves in Japan. The noses and ears were used to count the number of people who were killed by Japanese wariors as trophies.

After three years of failed negotiations, Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded Korea again. This time, he intended to annex the four most southern provinces of Korea – a much less ambitious goal than the first time. Just before the second invasion, Japanese used a plot to get Admiral Yi Sun-sin removed. They convinced the Joseon court that there would be a surprise naval invasion and they ordered Yi to attack first. Yi knew this was a trap and would not obey the order. Yi was dismissed, arrested and tortured. With Yi out of the way, the new naval commander took the entire naval fleet towards Busan, looking for the Japanese. On August 28, 1598, the Battle of Chilcheollyang took place and almost the entire Korean army was lost. King Seongjo fairly quickly understood his mistake and reinstated Admiral Yi.

The Japanese pushed rapidly into Jeolla Province. They attacked Namwon and there 3,726 Koreans died. We know this because Toyotomi Hideyoshi insisted that soldiers send back at least the nose or the ear of those killed. To this day, a little-known burial mound in Kyoto called Mimizuka (Ear Mound) that Hideyoshi erected sits as a reminder. The mound includes 38,000 Korean and 30,000 Chinese ears taken during the entire war. The phrase “they will cut off your nose” is still used in Korean to indicate a dangerous situation.

The Ming quickly sent troops and the combined Ming, Joseon, Righteous Army and warrior monks kept the Japanese from re-entering Hanseong and pushed them back to the south. In October of 1597, the reinstated Admiral Yi organized his only 13 remaining ships to attack the Japanese navy that consisted of 133 battle ships and 200 further support ships. In the narrow straight of Myeongnyang, Admiral Yi was able to hold off the Japanese navy and not lose a single ship.

Admiral Yi was able to prevent supplies from reaching the Japanese through the rest of the year. But after a Japanese victory in Ulsan in January of 1598, the two sides were at a stalemate. Several more Japanese victories in the south throughout 1598, but the entry of 75,000 Ming troops into the south brought a new stalemate. In September, Toyotomi Hideyoshi died and in October, the Japanese Council of Five Elders ordered all troops to return to Japan, though they kept Hideyoshi’s death a secret to not upend the troop’s morale.

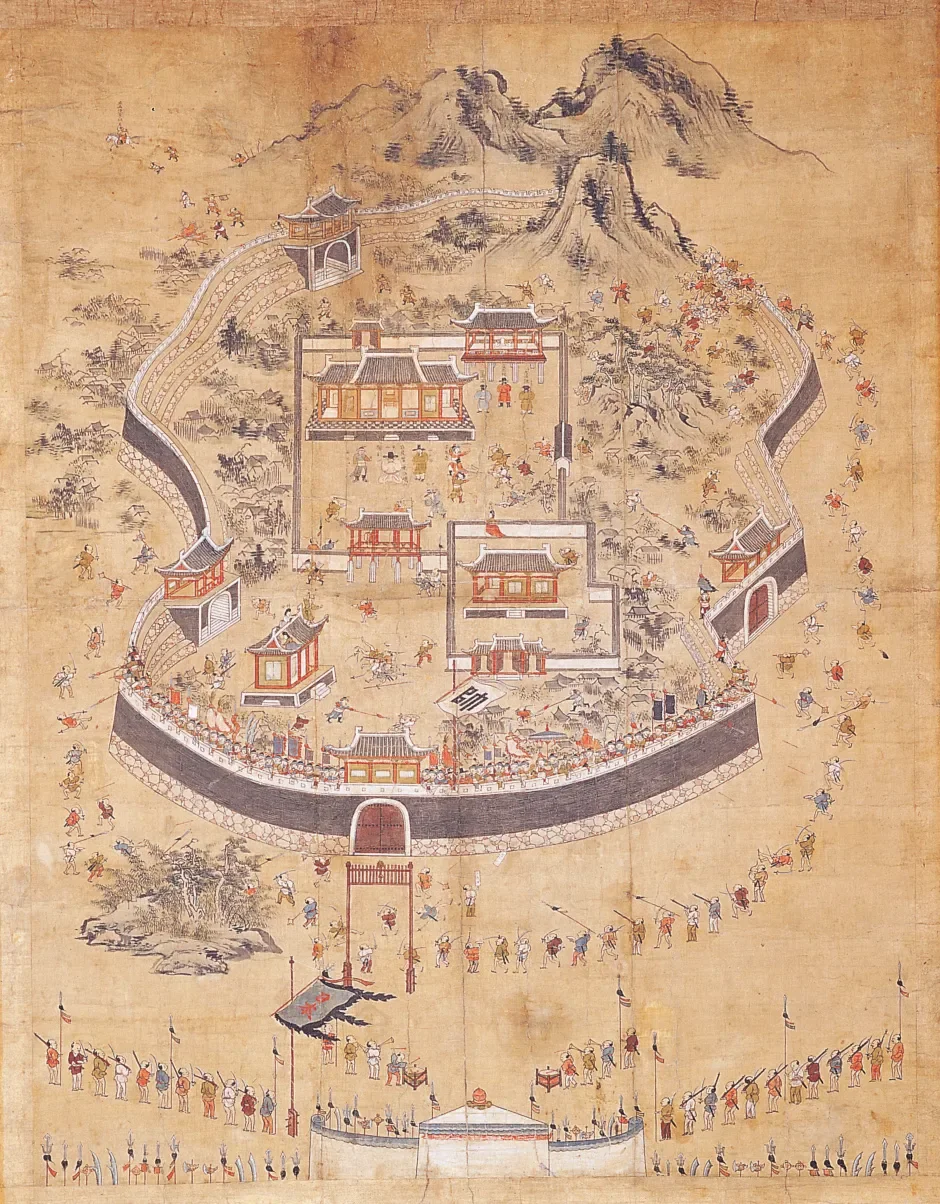

The final battle of the war was a naval one, the Battle of Noryang. It ended up being the bloodiest battle of the war. On December 16, 1598, the Ming and Korean navies made a surprise attack on the 500 Japanese ships at the Straight of Noryang. Both Yi Sun-sin and the top Ming admiral were killed, but the battle was an overwhelming victory for the Ming and Korea and a great defeat for Japan. Only 50 ships managed to escape. The last Japanese ships sailed away from Korea on December 24, 1598. This map shows how narrow the Straight of Noryang was.

Aftermath

Negotiations between Korea and Japan went on until 1606, when an agreement led to some Korean prisoners being returned and a form of diplomatic and trade relations between the two countries resuming, though trust was low and tensions remained.

The cost to the Ming, who had already suffered losses in their battles with the Mongols, was great and the end of the war was really the beginning of the end of the Ming Dynasty. Within 50 years, they were no longer in power. Poor grain storage and fluctuating weather put social pressures on the government. The financial investment in the war took its toll not only in loss of life, but financially as well.

The cost to Japan was more in war casualties than anything else. That, and the embarrassment of their defeat. No doubt the desire to change the outcome was at least one factor in the Japanese occupation three centuries later. The Toyotomi clan was weakened and lost power quickly after the end of the war and Hideyoshi’s death. The benefit to Japan, however, came in the appropriation of Korean craftsmen and scholars.

Suncheon Japanese Castle in Jeollanam-do

Agricultural land in Korea that had been devastated during the war took over two hundred years to completely recover. This set the foundation for many years of hunger, especially in Hanseong, which had shrunk from 100,000 residents to 40,000. The main palaces had been burned down. The destruction of libraries, temples, fortresses and the theft of artwork and writings cannot have a tangible value put on it. Japan still possesses many of the things it took and has not returned them. This loss of sacred, scientific, historic and scholarly artifacts and texts is horrible and creates a cultural hole that is irreparable. But the loss of the people, knowledge and artistry of Korean potters is an immeasurable and permanent loss. We will detail this below.

An interesting remnant of the war are the ruins of Japanese castles in the southern part of Korea. Some were built to secure supplies for the Japanese army and some were built to establish the government of Japan in Korea. You can visit these ruins and the Cultural Heritage Protection Act protects them as any other cultural site. If you visit Busan, you can find maps and more information about visiting both Japanese and Korean castle (fortress) ruins on the southern coast.

Pottery

Naesan Seowon in Younggwang, Jeollanam-do was built to commemorate work of Kang Hang.

One of the results of the Imjin War was that between 50,000-200,000 Koreans were taken as slaves to Japan. Many different kinds of craftspeople were taken to Japan, including goldsmiths, herbal medicine experts and potters. Korean scholars were also taken and one in particular, Kang Hang, played a key role in teaching the Japanese daimyo and introducing Neo-Confucianism to Japan. By far the most profound and long-lasting forced transfer of cultural knowledge was experienced by Korean potters.

Korean pottery was already well-known and sought after in both China and Japan, but also in Portugal, Spain and Holland. Korean’s work with pure white porcelain was envied everywhere. Much of the pottery in Korea was being produced in the far south, which is the area that was first and most consistently occupied and attacked during the war. There are few written records regarding the exact history of individual potters, since most were of the common class, but recent research examining pottery sites, pottery pieces and shards, reveals precise evidence about the history that is already well-known: Korean potters definitively and dramatically changed the course of pottery-making in Japan.

A written order by Toyotomi Hideyoshi said: “If, among the Korean captives, there are any craftspeople, embroiderers, or women who are skilled with their hands, they must be offered to me…” Korean craftspeople were distributed throughout Japan, but the potters were specifically placed in cities that produced pottery, particularly on Kyushu Island – the island furthest west and closest to Korea. The most prominent styles of pottery, including Hirado ware, Hasami ware, Arita Ware, Takatori ware and Satsuma ware, among others, all come from this island.

There were internal daimyo clashes taking place after the death of Hideyoshi. Japanese records show that the Koreans had difficulty with language and competed for scarce resources. In the records the Origins of Naeshirogawa, it is documented that Koreans tried repeatedly to return to Korea, but couldn’t because of rough seas. Because the Koreans were brought to Japan by force, they had to find ways to support themselves and their families. The potters did what they knew best – they made pottery. Koreans had unique recipes for their clays. Their pottery kilns that were wood burning, were physically longer, larger and burned hotter, producing stronger and more refined porcelain. The shapes of their pottery were unique. Their forms of decoration were unique. The formulas of glazes and their colors were unique. This tea bowl shows a poem written in Hangeul:

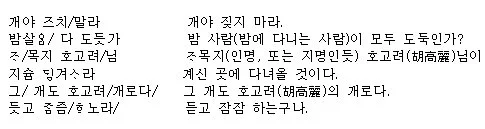

Poem on the tea bowl has been diciephered into modern Korean. The word 호고려 meant “barbarians from Goryeo” used by Japanese people. The word was used to refer to Joseon people who were kidnapped during the Imjin War. The poem can be translated as following:

Line by line translation by Eun Byoul Oh based on the article about the tea bowl and the poem.

Dog, do not bark

Do you think all the people who wanders during night are thieves?

(Either a person’s name or name of place) I will come back after I visit where Hogoryeo people are staying.

The dog must be a Hogoryeo dog too.

It listened and became silent.

Not only is the poem written in Hangeul, it is written in the Korean poetry format of sijo. It also is a copy of a well-known poem from Korea about a black dog.

Statue of Baek Pa-Sun in Arita, Kyushu, Japan

Almost immediately after the Imjin War, the Dutch East Indies Company was formed and traded goods from all over Southeast Asia to Europe. Japanese porcelain was one of its most sought-after of traded goods. These wares were all attributed to Japan, but the artistry was clearly Korean. Over time, the Koreans intermarried with Japanese and the pottery evolved. One wonders what could have happened if Korean potters had been allowed to stay in Korea and how the history of Asian pottery might have been different.

There is an older, but very good, K-drama about the first female Korean potter allowed to make pottery for the king. Neo-Confucian philosophical beliefs interpreted women involved in touching and creating something for the king as dirtying or corrupting it. But this particular potter, Baek Pa-sun, was so skilled, that she was allowed to make this most important pottery. She and her husband were captured during the Imjin War and taken to the Hizen Province of Kyushu where she was responsible for the creation of Arita ware. There is a commemorative plaque to her where she is buried in Arita and in 2018, a statue of Baek Pa-sun was installed in Arita to commemorate her contribution to Japan’s history of porcelain.

The K-drama Goddess of Fire about Baek Pa-sun is available to be seen on Viki.

The European Research Council has done extensive research into the influences of the Korean potters on Japanese pottery after the Imjin War. They have put together an impressive website that shows pottery and its connection to Korean styles and techniques city by city in the cities where Korean potters were taken. The website includes webinars and documents on other effects of the Imjin War on both Korean and Japanese culture. If you want to know more about this subject, including a searchable online database, you can visit the site here.

Further Reading

https://sydney.jpf.go.jp/japanese-studies/resources/aftermath-of-the-east-asian-war-of-1592-1598/

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1398/the-japanese-invasion-of-korea-1592-8-ce/

https://openkorea.org/history/imjin-war-and-the-aftermath-the-joseon-dynasty/

https://warhistory.org/@msw/article/imjin-war-1592-1598

https://www.coreaverse.com/2025/08/the-imjin-war-koreas-crisis-and.html

Influence on Japanese pottery

https://pacificasiamuseum.usc.edu/audio-tours/korean-influence-on-japanese-ceramics/

https://stonebridgepress.substack.com/p/the-korean-origins-of-japanese-ceramics-b63

https://japanchangemoney.com/News/View/historical-perspectives9974

https://www.thoughtco.com/ceramic-wars-hideyoshis-japan-kidnaps-koreans-195725