SPECIAL NOTE: History of Korean Presidential Elections

Tumultuous Saga of Korean Democracy

By Eun Byoul Oh and Sharon Stern

Korea’s new President, Lee Jae Myung, at Seoul National Cemetery for Korean Memorial Day Ceremony

In light of the June 3, presidential election in South Korea, our newsletter team has decided to give you an overview of the complex history of South Korean presidential elections. Democracies take time to form and the process can be messy. South Korea’s struggle toward finding democracy demonstrates this clearly.

As we have covered in many previous articles on political history and upheaval of South Korea, Korean Democracy has come a long way to create the current institution of a direct and free presidential election. The current form of direct election for a South Korean president was finalized as a result of the 6.10 (June 10) Democratic Struggle in 1987.

South Korea is currently under the Sixth Republic, which began with the amendment of the Korean Constitution in 1987. The last amendment of the constitution limits the president to a single five-year term and guarantees the people’s voting rights to directly elect the president. Below we summarize the complicated and tumultuous history of the South Korean presidential office and presidential elections.

Students participated in the 4.19 Revolution, a pro-democracy movement of 1960. The banner reads “Let’s die of righteousness and live in truth.”

The First Republic of South Korea had a single president, Syngman Rhee, who served three, full presidential terms until he was forced to step down after it was revealed that he had rigged the last election to maintain his control of power. Rhee held the position from 1948 until 1960. Rhee had studied and lived in the United States and was known by the US Government who structured South Korea’s post-war government. During the First Republic, South Korea had a Vice President, who was selected by Congress. The president was also originally selected by the Congress, until Rhee changed the voting system to a direct election for his second and third terms. He made this change when it appeared likely that the Congress would not re-elect him. Rhee‘s intention behind the change to a direct election system was ultimately to allow him to serve many presidential terms. Rhee amended the constitution to fulfill his greed for power. The National Assembly attempted to block Rhee’s constitutional changes, but Rhee had opposing Congressmen arrested and then passed the changes. In 1960, Rhee was elected to his fourth term, but when he announced that his choice for Vice President (decided in a separate election) had won by a huge margin, accusations of election fraud led to mass protests and the 4.19 (April 19) Revolution. Rhee stepped down after the eruption of student protests across the nation (see the April newsletter for more details).

President Park Chung Hee and Cha Ji Cheol during May 16, Coup in 1961. Cha became Park’s Chief Security Officer until both were assassinated.

With the end of the First Republic of Korea, the Second Republic began on June 15, 1960 and was a parliamentary-style government. Chang Myong was selected as Prime Minister (head of government) and Yun Po-sun was selected as President (head of state) by the National Assembly, not through a public election. The National Assembly was reorganized into bicameral chambers. The Second Republic was the only time that South Korea operated under a parliamentary governmental system. The Second Republic collapsed abruptly in 1961, after the May 16 military coup d’etat launched by Park Chung Hee, Korea’s 18-year long dictator.

The Third Republic of Korea began after the coup on December 6, 1961. Elections were held in December of 1961, after a national referendum was held to amend the Constitution and switch back to the direct election of the president. Park presented this as a return to civilian government, but was indisputably a dictator for his entire term in office. Park became the fifth president of South Korea. The Third Republic returned the National Assembly into a unicameral system, and enabled the president to serve two terms. The vice president was replaced with a presidentially appointed prime minister, and the cabinet system was abolished. The Third Republic ended in 1972, when Park Chung Hee launched a self-coup in October of 1972, dissolving the National Assembly, suspending the constitution and declaring martial law. The incident of the Self Coup is known as October Yusin or The October Restoration.

Busan-Masan Democratic uprising in October of 1979. Students rose to demand for end of Park’s Yusin government.

Park’s self-coup was launched with the primary intention to maintain power. He made “emergency” changes to the constitution that was finished on October 27 by the named emergency State Council and approved on November 21. This constitution was known as the Yusin Constitution. Yusin (유신; 維新) comes from the Chinese Hanja root meaning “restoration”. The establishment of a new constitution began the Fourth Republic of South Korea. The new constitution allowed the President to serve six year terms without any term limits. Under Park’s Yusin government, the president held the power to dissolve the National Assembly, to appoint all of the judges and appoint one third of the National Assembly members. The Yusin Government also changed the election process to an election by an organization called National Conference for Unification (통일 주체 국민 회의). The Fourth Republic was, in short, a government that was constructed to allow Park’s dictatorship to continue. Park tried to argue that a Western-styled democracy was not right for South Korea because it was still developing economically. He argued that the Yusin Government was a way to guarantee stability.

The Fourth Republic of Korea transitioned into the Fifth Republic after Park’s assassination, and the December 12 coup d’etat launched by Hanahoe (하나회 - Group of One) - a secret military society, led by Chun Doo Hwan. Chun continued to run the government as a repressive dictatorship and public freedoms were further crushed when Chun’s government expanded martial law on May 17, 1980. The Seoul Spring— the brief period between Park’s assassination in October of 1979 until the Gwangju Uprising on May 18, 1980— was brutally suppressed by the new military-led government. Chun was selected (rather than elected) as the 11th President of South Korea on August 27, 1980 by the National Conference for Unification.

Student protester Lee Han Yeol was murdered after a head trauma while he was protesting for democracy.

The Fifth Republic underwent yet another constitutional change that extended the presidential term to seven years, but limited them to a single term. The Fifth Republic established an Electoral College which conducted indirect elections. The Chun government, Chun’s cronies like Roh Tae Woo and the newly imposed constitution controlled Korea under strict censorship and limited the people’s right to participate in politics. In addition, politicians from other political parties were prohibited from taking part in political activities. Despite the supposed “multiparty” government, Chun’s government was a one-party dictatorship. From the Gwangju Uprising (see the May newsletter) in 1980 until the end of the Chun government in 1987, many South Koreans lost their lives protesting Chun’s brutality and oppression. Many student activists, including Park Jong Cheol and Lee Han Yeol, were tortured and murdered in the midst of the political struggles. Chun’s government was only forced to resign after prolonged student and labor protests calling for democracy.

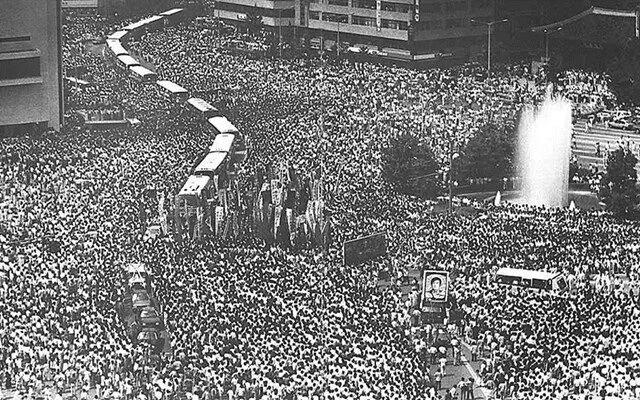

From June 10-29, 1987 the June Uprising took place. This was a nation-wide pro-democracy movement that saw mass protests across the country. On June 10, Chun Doo Hwan announced his hand-picked successor, Roh Tae Woo, as the designated next president of South Korea. Although student and labor protests had been taking place for a long time, this announcement and its obvious delay in allowing direct elections, was a last straw for the country. Mass protests erupted. The upcoming 1988 Olympic Games made Chun choose between implementing more violence and repression or conceding to public demand for direct elections and the reinstitution of civil liberties.

On June 10, 1987, mass protests erupted accross Korea. The 6.10 Democracy Struggle forced Chun to step down from power.

On June 29, Roh made the June 29 Declaration, promising free elections, competitive candidatures, amnesty for political prisoners, establishing the right of habeas corpus, freedom of the press and other social reforms. Although later debated as a political tactic to calm the protests, the rights laid out in the June 29 Declaration became the foundation for the new constitution and the establishment of the Sixth Republic, which is still the current Republic of South Korea. Roh was elected by popular vote, though barely, but the beginning of true democratization in South Korea had finally begun. Thanks to these changes, the people of South Korea have the right to directly elect their president today. The South Korean people’s journey to their present-day voting rights was indeed a turbulent one, passing through multiple brutal dictatorships. However, the South Korean people prevailed through perseverance and resistance.

Unfortunately, on December 3, 2024, South Korea once again witnessed how fragile democracy can be. President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law in yet another South Korean attempt at self-coup. Fortunately, democracy has held on as Yoon was arrested, impeached and his trial for insurrection is on-going. He still has many supporters in the country, however. Another reminder that democracy is a precious and fragile thing. In fact, democracy is really like a plant, needing constant attention, feeding and care. The democracy that we have cannot be taken for granted, but it is something that we need to vigilantly protect and cultivate. The people of South Korea need to be the watchdogs for its government to decide its leader as the only true sovereign of the country.