KOREAN-AMERICAN VOICES: Jean Vavra’s Story

By Jean Vavra

Between Two Worlds

I am a first-generation Korean American, raised between two worlds that didn’t always know how to speak to each other—but somehow taught me how to listen.

My parents both came from large families in Korea and were the only ones brave enough to leave everything familiar behind. They arrived in America carrying more than suitcases: they carried hope, fear, and a deep sense of responsibility. Wanting us to succeed in a country that often measured worth by how well you blended in, they made a difficult choice. They didn’t teach us Korean. They wanted us to assimilate, to be American, to do well in school, and to never be held back by an accent or a misunderstanding. That decision came from love, even if it cost us something.

Our first home was in Smithtown, New York, far out on Long Island. At the time, my family was the only Asian family in town. Our differences were impossible to hide. In first grade, kids would ask me to open and close my eyes over and over, trying to figure out why they looked the way they did. I didn’t yet have the language to explain identity or the confidence to defend it. I only knew that I was being noticed for something I hadn’t chosen—and didn’t quite understand.

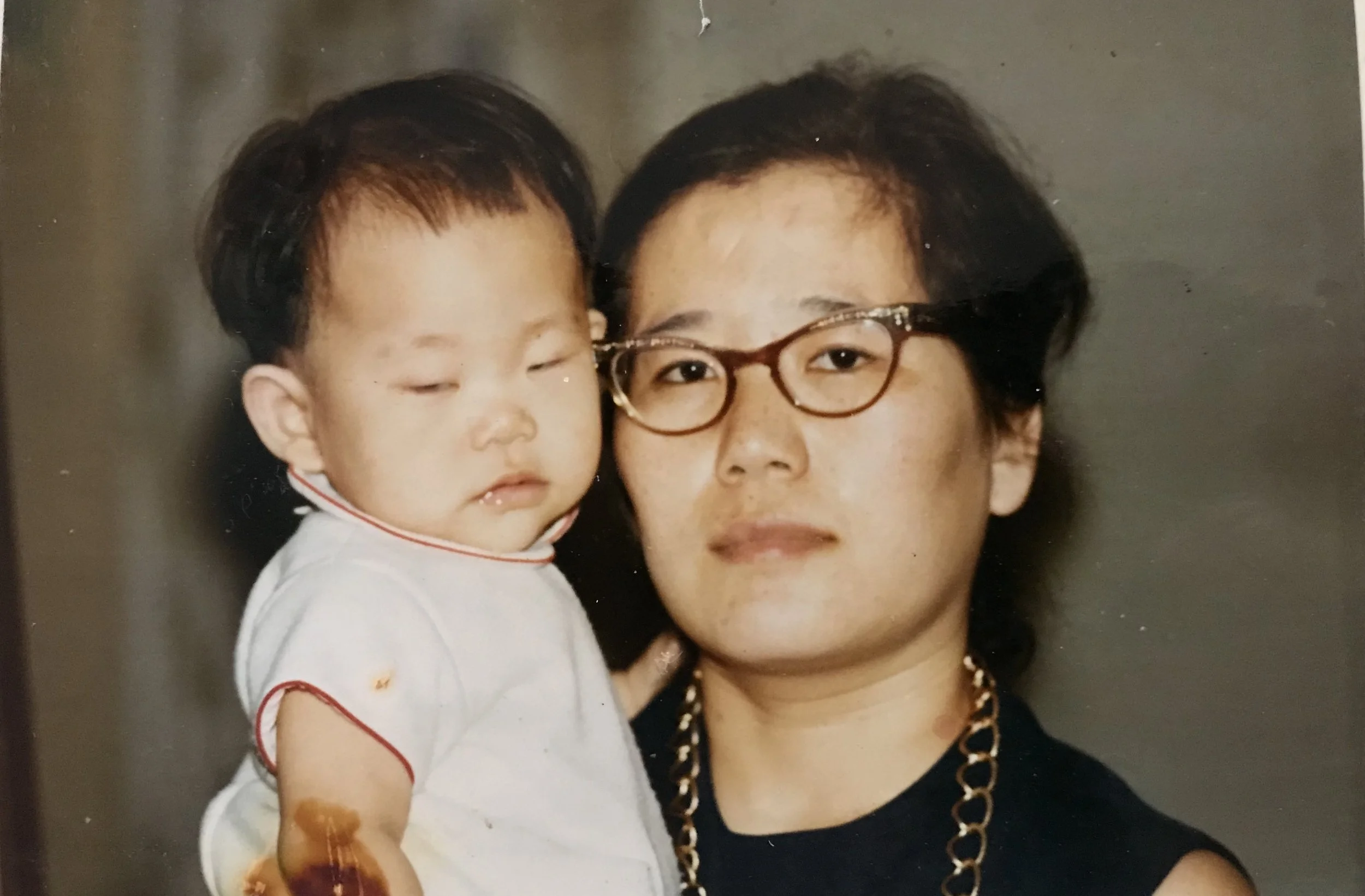

My mom stayed home to raise us. Looking back, I see now how much strength that took. At the time, though, I’m sad to admit that I was often embarrassed by the small ways she was different from my friends’ mothers. Her English wasn’t fluent. She dressed differently. She moved through the world with a quiet humility shaped by sacrifice. I spoke no Korean, and she struggled with English, so the space between us sometimes felt wider than it needed to be. We loved each other deeply, but we couldn’t always say everything we wanted to. That is one of the quiet heartbreaks of immigration—the love that exists beyond words, and the words that never quite arrive.

After my mother passed away, I traveled to Korea. There, I learned something that reframed everything I thought I knew about her. Before coming to the United States, she had been a doctor—at a time when not all women even went to college. She had built a life of achievement and purpose, and then set it down to give her children a different future. Her sacrifices were not born of limitation, but of choice.

While I was in Korea, something extraordinary happened.

I don’t know if it was a dream or her spirit, but I saw her. She was smiling at me, the way she used to, full of warmth and quiet pride. I said, “I’m proud of you, Mom.” And she replied that she was proud of me too. In that moment, something healed. I realized that my story is not one of loss, but of continuity. I carry her courage even if I didn’t always recognize it. I carry my parents’ dreams, even when I’ve had to redefine them for myself. Being a first-generation Korean-American means living with complexity—gratitude and grief, belonging and distance—but it also means inheriting an incredible resilience.

Today, I understand that I am not divided between cultures. I am built from both. My parents’ journey didn’t erase who they were—it made who I am possible. And in finally seeing my mother clearly, I learned to see myself with pride too.