BOOK CLUB REPORT - Sept 2025

By Casey Eckersley

KCCNYC Dosan Hakdang August Meeting

On August 24, the Dosan Hakdang book club was introduced to a collection of work by renowned Korean resistance poets. In celebration of the 80th anniversary of Korean independence, our group took time together to appreciate the beauty of the golden age of Korean poetry. Four resistance poets were introduced, highlighting several of their poems in translation.

Yun Dong-Ju

Yun Dong Ju, Korea’s most beloved poet.

First we discussed two works of Yun Dong-Ju: 서시 (“Prologue”) and 별 헤는 밤 (“A Night of Counting Stars”). Generally considered the favorite of the group, we were taken with the musicality of his poems. The language of his poetry felt more human and less overtly political. The emphasis in 별 헤는 밤 on the everyday things he loved and longed for felt like a reminder that even during impossible times, there is still underlying joy and beauty to give life meaning.

Of course, this emphasis is also a reminder of all the things that were lost to Yun Dong-ju, which can bring a new depth of empathy from those of us who have never personally experienced such hardships. In particular, the repeated emphasis on names (“green grass will proudly bloom on the hill where I buried my name”) took on new meaning when we learned that Yun Dong-ju was forced to adopt a Japanese name under colonial rule - a literal erasure of identity, the most personal thing that can be taken.

(Unserious aside: as someone who has been forced to listen to the University of Oklahoma fight song more than once, I still cannot get over the fact that Yeonsei University uses 서시 as a fight song. Truly an inspirational cultural moment)

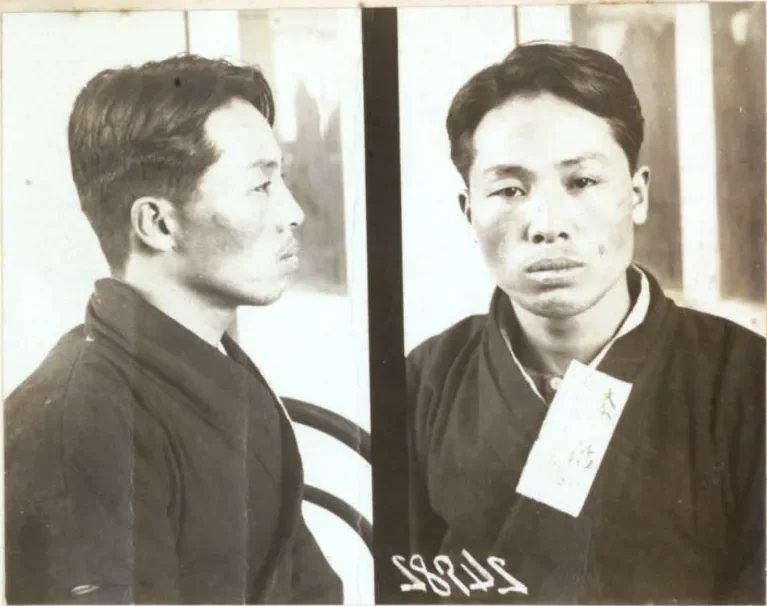

Lee Yuk Sa

Yi Yuksa, he was a resistance poet and an active independence activist. He was arrested 17 times until he died.

We discussed two poems by Lee Yuk Sa: 교목 (“A Tall Tree”) and 광야 (“The Wilderness”). In our group, Lee Yuk Sa was an understated favorite. Eun noted that “The Wilderness” was the toughest to translate for our group. In translation, it storms in ready for a fight, solemn and unflinching (“like Genesis” according to some, “like metal lyrics” to others.) We learned that Lee Yuk Sa was a revolutionary militant, which helps to understand the vehemence in his writing.

In discussion, we learned that his daughter’s name, 이옥비, is rooted in the Hanja for infertile land. His daughter was quoted as saying that her name was the only thing her father left her. In this context, even within the militancy of the poem, there could be something beautiful in the phrase "Let me sow the humble seeds of my song.” We hope that perhaps here he meant to indicate optimism that his actions would restore the fertile lands of his home for a better future for his daughter.

Lee Sang Hwa

Lee’s poems used vivid imageries and personification. He was influenced by western literature, particularly French literature. Lee was also a translator and his worked on translations of Korean folktales and stories of Korean tradition until he died of cancer.

The poem 빼앗긴 들에도 봄은 오는가 (“Would Spring Return to the Stolen Field?”) inspired the deepest discussion, with the most hidden meaning to discuss. We discussed the ambiguity in the term 푸른 in translation and Eun’s choices in capturing blue and green. We discussed the repeated references to hair and how that might be related to the forcible cutting of Korean hair during Japan’s occupation. We discussed who the intended listener might be - who was Lee Sang Hwa posing these questions to with such desperation?

Many in the group appreciated the beautiful imagery of the poem, evoking such a detailed adoration of his home, which made the loss elicited in the closing line all the more heartbreaking (“But now - since our field has been stolen, spring would also be taken away.”)

Sim Hun

Sim Hun was imprisoned for his involvement in March 1, movement. Despite his family’s pro-Japanese colonial stance, he continued his independence activist work. He also wrote the novel Evergreen and he also wrote film scripts.

Finally, we discussed 그날이 오면 (“When the Day Comes”). Sim Hun’s fans in our group appreciated how straightforward this poem felt; his frustration comes through cleanly. We learned that this might be a byproduct of the timing of his writing. This poem was written relatively early in the Japanese occupation at a time when the colonial government encouraged Korean writing to keep a finger on the pulse of the Korean public. Later, suppression of the Korean language intensified, which may have led to the more restrained poems of Lee Sang Hwa and Yun Dong-ju.

Regardless, it’s hard to read this poem and not want to incite a revolution. “If I could ever hear the thundering roar of the people, even once, I would gladly stumble and die on the spot.” The times were dark, but the words of rebellion are truly unparalleled.

You can read Eun’s wonderful translations of the poems here.

KCCNYC’s instagram team has been curating the poems throughout month of August. See the posts here.

September DOSAN HAKDANG: the Disaster Tourist

In September, we will be reading “The Disaster Tourist” by Yun Ko-Eun (translation by Lizzie Buehler.) This late-capitalist satire takes on the tourism industrial complex, the Me Too movement, and the dangers of complicity in a tight 200 pages (with a shocking plot twist that you won’t see coming!) We will be meeting on September 21, 2025 at 2PM (Eastern) and would love for you to join!

RSVP to join us is available here.

It was great to see you all at the book club! We even had some members joining from Canada and Albania. :D Hope to see you all at the next book club!