KOREAN DIASPORA VOICES: Justine’s Story

By Justine Velasquez

Justine’s Family

I spent my childhood in Quezon City, Philippines — born and raised in its hot and humid tropical climate, its busy streets filled with children running around. I had a fairly typical Filipino childhood, filled with memories of helping my grandmother pick out the tiny stones from uncooked rice under the late afternoon sun, getting scrapes on my knees and elbows from playing roughly, doing my homework by candlelight when the electricity would go out. But I realize now that there was something quite out of the ordinary during my childhood in the Philippines in a very specific way: we always had a big jar of homemade kimchi in our fridge. I never thought much of it before. That jar was just always there, mysterious in its origins. Try as I might now, I am unable to conjure up images of the kimchi being made. How was it made? When was it made? Where was it made? What was it made of? Though I was blissfully unaware of it at the time, my grandmother would have made that kimchi from scratch, in the way that my great-grandfather had shown and taught her.

My maternal grandfather was not present in our lives. The one paternal figure my mother had was my great-grandfather. He was the one who scolded her for any perceived wrongdoing when she was a kid. He was the one who walked her down the aisle when she got married. Naturally, my great-grandfather became the quintessential grandfather figure to me. One of my core childhood memories is sitting on his lap while he was on his rattan rocking chair, offering me a sweet treat (usually in the form of a pre-packaged cake). It was difficult to communicate with him, given his old age and broken Tagalog, but I always felt his affection in those small moments of silent companionship. He was the only one I ever called lolo (“grandfather” in Tagalog). I always thought my lolo was just like all my friends’ lolos. When he passed away in 2000, I vaguely remember some public figure related to politics at that time visiting during his wake. As a kid, I only fleetingly wondered why some man whom I would see on the news was there to pay his respects to my lolo.

-

We have more for you. During the Pacific war, the Koreans who were scattered across the South East Asia. They were either forcibly conscripted by the Japanese Colonial regime, or were sacrificed as a human shield in the battlefield.

Thankfully there were people who survived, but the survivors were not able to make it back to main land Korea. Although 50 years have passed since the war has ended, there are people who are living abroad with traumatized memories. Reporter Han Jae Ho got to meet him.

In Caloocan City, which is about 20 Kilometers from Manila there is an old house, about 71.1663ft2 sized, of Mr. Jang Dae-Gil down the narrow alley.

Hello Mr. Jang (할아버지 안녕하세요)

Hello (네)

He is 88 years old this year. The tragedy started when he moved to Philippines after being conscripted by the Japanese. He was told lie that he would earn a lot of money when he goes to South East Asia and left his hometown, Uiju.

They told me to work, so it was impossible for me to not go to work.

So I worked.

In Chinatown of Manila, Jang’s hometown friend had a pharmacy, Goryeo Pharmacy, where Mr. Jang spent a long time meeting with Koreans who were forcibly brought over to Philippines during the wartime, longing for his hometown in a foreign country.

I want to go to my hometown, my home, since I do not know how much time I have.

When darkness falls onto Manila, the footsteps of Japanese colonial army, going to Comfort Women Camp (위안소) rang the air of the city.

The dilapidated building behind me was where the comfort women camp stood. Although we could not find a trace of it now, Mr. Jang provided his witness accounts of the devastating lives of Korean Comfort women.

During the holidays and Saturday evening, many of them came. I asked (Comfort Women) if they didn’t want to go home. They said they wanted to go as quickly as possible, but they cannot go.

Mr. Jang remembers the brutal memories of the war, he holds sorrow and grudges from the memories. The hometown he desperately wanted to go back is now blocked by the 38th parallel.

When he feels devastated that there is no way to go back to his home, Mr. Jang holds his youngest daughter’s hand to go to the beach.

I want to go back before I die. I don’t know when reunification of Korea would happen. I want to go back to my hometown as soon as the reunification happens. I have my home and my land there.

From Manila, KBS News Han Jae Ho

Curiosity found me again a couple of decades later, after spending a few more years in the Philippines, immigrating to the United States, and making my own way to where I am now, in New York City. I started consuming Korean entertainment (a quick shoutout to Netflix’s wide array of available dramas for being the catalyst) and was inspired again to explore my family’s past. I did have sudden short spells of curiosity here and there before, where I would try to look him up, but quickly gave up because I couldn’t find anything at all. My relatives were not very helpful in providing reliable information either. As far as everyone knew, he was originally from Seoul and then moved to Manila as a soldier. Then I started studying 한글 (Hangeul, the Korean alphabet) and had the long-overdue realization that looking up his name in 한글 would probably yield actual results. 장대길. I also added “필리핀” (Philippines) in the search bar for good measure. Lo and behold, an old KBS news clip from 1995 with a familiar face in the thumbnail popped up. There he was — my lolo. And the actual truth of his life.

The video starts off with a KBS (Korean Broadcasting Station) news anchor talking about a Korean man in the Philippines who bore witness to the atrocities of the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. Then a cramped apartment somewhere in Metro Manila, where my great-grandfather lived at the time.

장대길 (Jang Dae-gil) was born in 1907 and raised in 의주 (Uiju), in what is now North Korea. During World War II, the Japanese Imperial Army came to his town. With the false promise of earning a lot of money, the army convinced him to join and leave 의주. Eventually, he would be sent to the Philippines to perform forced labor for the Japanese Imperial Army.

In the Philippines, he suffered at the hands of the Japanese Imperial Army, yet he was still considered one of the lucky ones. Others were forcibly conscripted to essentially be human shields. My lolo saw Korean comfort women being kept in a building in Manila, where the Japanese soldiers would come on Saturday evenings when they weren’t on duty. All he could do was whatever work the Japanese Imperial Army commanded him to do. Whenever he would see the soldiers, he would ask them if he could go back to his hometown as soon as possible. He said he couldn’t live in such circumstances. Of course, they never granted his pleas. He did find some solace among compatriots. He frequented an establishment called 고려약국 (Goryeo Pharmacy), which was run by a friend who also came from 의주. This community must have been like an oasis to him, helping quench his intense thirst for home in such an unforgiving environment.

Even after the war, he still could not return to his hometown. The 38th parallel was drawn and 의주 was on the northern side of it. While most of his compatriots returned to Korea, he ended up staying. He also started a family in the Philippines. Throughout the years, the Korean embassy in the Philippines kept tabs on him. My mother would talk about how they would send him gifts like Korean pears during holidays and apparently even sent him to Korea once to participate in a special event.

-

An overseas Korean has been asking our broadcasting system if he would be able to search for his lost family. He was able to reunite with his family after 40 years. Reporter Heo In Gu reports on the reunion.

Despite his old age, Mr. Jang Dae Gil, 82 years of age, came to Korea to participate in the Overseas Korean event. He was able to reunite with his daughter Mrs. Jang Sung Sook and her family who came to meet him at his lodging this evening. They were able to share 40 years long of longing and affection.

Though there was some awkward moments of unfamiliarity due to the long years of separation, the family shared tears as they recounted on their biological family ties.

Mr. Jang moved to Philippine under the sufferings of Japanese colonial regime. There was no way to find each other for the last 40 years, so they assumed each other to be possibly dead. The family saw the report from MBC last night, and they were finally able to reunite. Their neighbors suggested that the family should contact the broadcasting system.

I did not even know if they were alive or dead, but I am so thankful that I got to meet them.

I am so pleased to meet him. I thought due to his age, old man must have died, but I am just praising god that he survived. He is very old now.

Further research brought me to another news clip dated 1989, from MBC (Munhwa Broadcasting Company) this time. This was when he was chosen to go to Korea to participate in the Korean National Sports Competition. During this trip, my lolo reached out to MBC, asking for their assistance in finding his daughter in Korea, with whom he has not had contact for over 40 years at that point. MBC was able to find her, who was by then living in 안양 (Anyang), just south of 서울 (Seoul). In that two-minute clip, I witnessed my lolo cry tears of both grief and relief, meeting the only daughter he was forced to leave behind during the war. This gave me even more perspective on the loss that weighed heavily on him since leaving 의주. He carried this heartache on his own for decades, with no certainty that he would lay eyes on his eldest daughter ever again.

I also found a news article from 부산일보 (Busan Ilbo, which is a Busan daily newspaper) covering the Korean National Sports Competition. It briefly mentions my lolo also reuniting with the younger brother of a friend he lived with in the Philippines. It adds that he was a kite-flying player in the competition. I never knew that my lolo liked flying kites. I enjoyed learning about this, yet I also felt a peculiar sense of sadness. Did he fly kites all the time while he was growing up in 의주? He must have, since he was invited to participate in the competition. I am reminded of all the things I don’t know and may never know about his life before coming to the Philippines. I still feel like I barely scratched the surface.

Nevertheless, these few revelations about my lolo made a significant impact on me. I found a new sense of kinship with him, many years after he’s been gone from this world, along with his (then) secret hopes and scars. He found himself in an unfamiliar place, far from home, away from those he knew his whole life, and had to quickly find his own two feet in a new environment to survive — as my mother and I needed to do when we first moved to the United States. My heart broke for him after seeing how much he longed for a home that he couldn’t go back to. Though he left 의주, 의주 never left him. I wish I could somehow help fulfill his wish of going back home. In the meantime, I made a promise that I would honor his history, our family’s history, however I can from wherever I am.

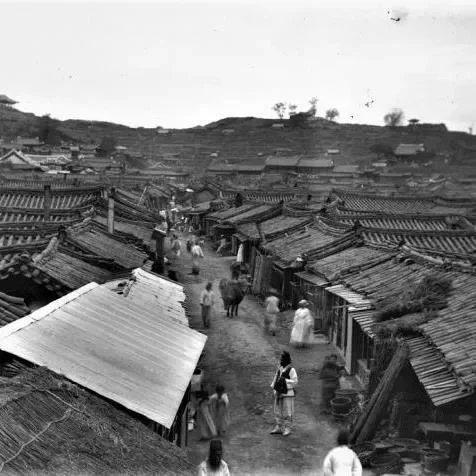

Uiju, present day North Korea, during the Japanese colonialism.

I never imagined that I would find a way to fulfill this promise within the confines of my Brooklyn apartment. It’s where I study Korean. It’s where I talk to my mother on the phone for hours about her memories of my lolo. It’s where I spend late nights searching for any bit of information about him online. It’s where I attempt to create my own versions of his dishes such as 냉면 (naengmyeon, a favorite of his), piecing together makeshift recipes through word-of-mouth descriptions from my relatives and my own research. It’s also where I started making 김치 from scratch, which is now a staple in my own fridge. After all these years, I am finally demystifying the origins of that elusive 김치 from my childhood — everything that had to happen for it to find its way into that fridge in our old apartment in Quezon City.